Adapted from The Triumph of Nancy Reagan, Simon & Schuster 2021.

In mid-1981 the U.S. Center for Disease Control noticed a set of medical curiosities: an alert from Los Angeles that five previously healthy young men had come down with a rare, fatal lung infection; almost simultaneously, a dermatologist in New York saying that he had seen a cluster of unusually aggressive cases of Kaposi’s sarcoma, an obscure skin cancer. These seemingly unconnected occurrences had two things in common. First, all of the victims were sexually active gay men. Second, their maladies pointed to a catastrophically compromised immune system.

About a month after those reports, a San Francisco weekly wrote that something it called “gay men’s pneumonia” was going around. By September 1982, there was a medical name for it: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or AIDS. The following May, scientists identified the retrovirus that was causing it: human immunodeficiency virus. HIV. It would take longer before it became clear who was at risk, how far the disease could spread, or what needed to be done to stop it.

“At first, we thought it was gay men, and then it was intravenous drug users, and then that it was Haitians—which was a mistake,” said Anthony Fauci, who was a senior investigator at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) until he became its director in 1984. As the number of cases mounted, Fauci submitted an editorial to The New England Journal of Medicine in which he warned against assuming that AIDS would stay confined to the populations in which it had first appeared. But at that point, not even scientists were ready to accept how ominous the signs were. Fauci’s article was rejected because a reviewer for the medical field’s most prestigious publication deemed it to be too alarmist. It subsequently appeared in the June 1, 1982, issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Nor was the story of dying gay men getting much traction in the mainstream media. Though more than half of those stricken were residents of New York City, The New York Times wrote only three stories about AIDS in 1981 and three more in 1982—all of which went on the inside pages.

The Reagan administration responded with massive budget cuts to public-health agencies, including the Center for Disease Control. The National Institutes of Health (NIH), the nation’s main backer of biomedical research, was also struggling with a funding squeeze.

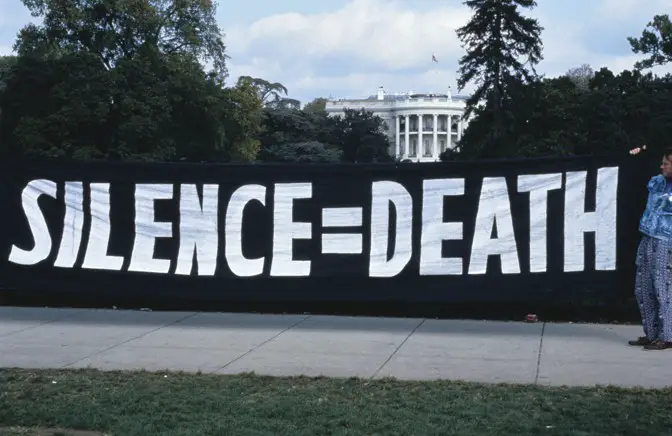

The president of the United States did not so much as publicly utter the name of the disease until September 1985. Even then, it was only because a reporter brought it up at a news conference. Not until the spring of 1987 did Reagan give a major speech about AIDS. By that time, the disease had already struck 36,058 Americans, of whom 20,849 had died.

The Reagan administration’s unwillingness to recognize and confront the AIDS epidemic has gone down in history as one of the deepest and most enduring scars on its legacy. What wasn’t known at the time was that, as the death toll mounted, a pitched battle ensued within the Reagan White House—and within the Reagan family—as First Lady Nancy Reagan and her son, Ron, tried to shake the president out of his complacency. It was a battle that pitted the two of them and a handful of allies against his hard-right advisers, who believed that AIDS should be dealt with as a moral and religious challenge, rather than a health crisis.

Those who would defend the Reagans would insist that the administration’s failures to confront the epidemic were not the result of deep-seated bigotry on the part of the president and first lady. Coming from Hollywood, the Reagans had many acquaintances who were gay, and they were comfortable in their company. Nancy, in particular, counted numerous gay men among her closest confidants. She was on the phone nearly daily with her friend Jerry Zipkin, the New York society gadabout. Her decorator Ted Graber slept in the White House with his partner, possibly the first acknowledged same-sex couple to do so. She was also sensitive to the specific dangers that gay men faced in society. When the author Truman Capote was arrested in Anaheim for disorderly conduct in the early 1980s, Nancy put in a frantic late-night call to Deputy White House Chief of Staff Michael Deaver, and begged him to find a way to get the renowned writer freed.

As far back as 1978, Reagan had been willing to risk his political capital with social conservatives by opposing a California ballot initiative that would have barred gays and lesbians from teaching in the state’s public schools. His opposition helped sink the ballot measure. But Reagan believed that homosexuality was sinful. In the spring of 1987, he discussed the AIDS epidemic with the biographer Edmund Morris and said that “maybe the Lord brought down this plague,” because “illicit sex is against the Ten Commandments.” Privately, Reagan trafficked in homophobic stereotypes, as did those around him. His press spokesperson, Larry Speakes, recalled that after the president’s weekly shampoo, Reagan would flick his wrist and tell aides in a lisping voice, “I washed my hair last night, and I just can’t do a thing with it.” Speakes wrote admiringly, “He does a very good gay imitation. He would pretend to be annoyed at someone and say, ‘If those fellows don’t leave me alone, I’ll just slap them on the wrist.’” Speakes himself cracked a homophobic joke when the reporter Lester Kinsolving asked him during an October 15, 1982, press briefing whether the president had any reaction to reports that 600 people had contracted the “gay plague.” It was the first public question the White House had received on the subject. The press secretary’s response: “I don’t have it. And you? Do you?” The reaction from the assembled reporters was laughter. At subsequent briefings over the next two years, Kinsolving, who was considered a gadfly, continued to press the White House spokesman about AIDS, only to be met with dismissive wisecracks questioning the reporter’s own sexual orientation. And the White House press corps continued to find these exchanges hilarious

In October 1986, The Washington Post’s Bob Woodward reported that during a meeting with his national security advisers, Reagan had made note of the Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi’s partiality for eccentric clothing and quipped, “Why not invite Qaddafi to San Francisco, he likes to dress up so much?” To which Secretary of State George Shultz replied, “Why don’t we give him AIDS!” According to Woodward, others around the table thought this was extremely amusing. San Francisco officials demanded an apology, both to the city and to people infected with the disease.

As was the case with many Americans during the early years of the epidemic, the Reagans’ practical understanding of AIDS was colored by fear, ignorance, and scientific uncertainty. One day, when the hairdresser Robin Weir was making one of his twice-a-week visits to the White House, Nancy inadvertently took a sip from his water glass. Afterward, she went to the White House physician John Hutton in a panic, worried that she might have contracted the disease. Hutton tried to reassure her that it was impossible to get AIDS that way, but she wasn’t satisfied. “How do you know?” Nancy demanded. “How do you know?” Weir died in 1993 at the age of 45 from what his obituaries described as a combination of colitis, bacterial sepsis, and a heart attack, all three of which are often associated with AIDS.

[Tim Naftali: Ronald Reagan’s long-hidden racist conversation with Richard Nixon]

But it is also clear that Nancy became attuned to the seriousness of the epidemic earlier than the president did—in part because her son was seeing it up close. “I’m in New York; I’m dancing [with the Joffrey Ballet]; I know people who are HIV-positive. Dancers, fashion designers, people like that,” Ron said. “I would talk to her about people, how many people, who these people were. And she began to understand that this is a big deal. This is a crisis. She began to sense that pretending this isn’t happening is not a good way to go.”

Nancy and her son began looking for opportunities to discuss AIDS with Reagan. “We’d start mentioning it, bringing it up as a topic, starting to get it into his head,” Ron recalled. He acknowledged that their effort did not get very far with his father. Where Nancy “could appreciate things a little bit more abstractly, it very much helped if he could put a face on something,” Ron said.

In 1985 the epidemic did indeed gain its face: the once-magnificent visage of the actor Rock Hudson. When Hudson was revealed to be dying of AIDS, “the whole picture changed” for the president, Ron said. During the 1950s and ’60s, Hudson had been one of the country’s biggest movie stars. But while Hudson wooed Elizabeth Taylor, Lauren Bacall, Gina Lollobrigida, and Doris Day on the screen, he lived a closeted existence off it. If the world had known that the man that fan magazines declared to be Hollywood’s most handsome star was gay, Hudson’s career would have been destroyed.

The first lady, given the acuity of her radar and her gossipy network of California friends, surely was aware of Hudson’s secret life. Reagan probably knew about it too. Hudson attended a state dinner in May 1984, and Nancy noticed that he looked gaunt. When she expressed concern about his health, Hudson told her that he’d caught the flu while filming in Israel but had recovered and was feeling fine. A picture from that dinner in her White House scrapbook shows Hudson beaming alongside the first couple, his hand clasped with Nancy’s. Afterward, Nancy sent Hudson a set of photos from the evening. She enclosed a note suggesting that he have a doctor check a red blotch that one image showed on his neck. It had been bothering him too, so he did, in June. The skin irritation turned out to be Kaposi’s sarcoma, and that was how Hudson learned that he had AIDS. By the summer of 1985, the 59-year-old actor’s deterioration had become obvious. He made an appearance in Monterey, California, with Doris Day, with whom he’d co-starred in some of the most popular romantic comedies of his day. Reporters and friends were shocked at how frail he looked. When Hudson collapsed in the lobby of the Ritz Hotel in Paris in July, his publicist put out a statement that he had inoperable liver cancer. The American Hospital in Neuilly-sur-Seine, where he was rushed, blamed his condition on “fatigue and general malaise.” But news reports shot across the globe speculating that it was AIDS and that Hudson had come to Paris seeking a miracle cure. In 1985 there was no effective treatment for AIDS; the first AIDS drug, AZT, wasn’t approved until two years later.

The White House announced that the president had telephoned Hudson to wish him well “and let him know that he and Mrs. Reagan were keeping him in their thoughts and prayers.” In Reagan’s July 24 diary entry, the president indicated that he had not known the nature of Hudson’s malady when they spoke: “Called Rock Hudson in a Paris Hospital where press said he had inoperable cancer. We never knew him too well but did know him & I thought under the circumstances I might be a reassurance. Now I learn from TV there is question as to his illness & rumors he is there for treatment of AIDS.”

After this entry, Reagan’s diaries do not mention AIDS again for nearly two years. On the same day the president spoke with Hudson, the White House received a desperate appeal for help in arranging a transfer for the actor to a French military hospital. The telegram from Hudson’s publicist, Dale Olson, which was addressed to Reagan’s assistant press secretary Mark Weinberg, claimed that the hospital was the one facility in the world that could provide the “necessary medical treatment to save life of Rock Hudson or at least alleviate his illness.” The hospital’s commander had turned down Hudson as a patient because he was not French, but the telegram said Hudson’s doctor “believes a request from the White House or a high American official would change his mind.” Weinberg took the matter not to the president but to Nancy, and the two of them agreed to refer it to the American embassy in Paris.

In later years, AIDS activists and Reagan critics would say that the first lady was callous in how she handled it. But it is also possible to appreciate that Nancy had been put in a situation where she had no good option. She was not averse to making discreet interventions on behalf of friends in trouble, as she had when Capote was thrown in jail. But Hudson’s illness was one of the biggest stories in the world at that moment. Had Nancy done a special favor on behalf of someone rich and famous while tens of thousands of others were dying of the disease in obscurity, she would have been justifiably criticized for that as well. Probably more so. There was also precedent to think about: No doubt, this would not be the last such request they would get. Was that kind of intercession on behalf of her friends a proper role for a first lady?

Despite the claims made in the telegram, it does not appear that the French hospital could have helped Hudson. According to And the Band Played On, a definitive book on the early years of the AIDS epidemic by the journalist Randy Shilts, when Hudson’s French doctor saw his patient’s dire condition, he concluded that any further treatments would do no good. Hudson spent $250,000 to charter a Boeing 747 and went home to Los Angeles, where he would die two months later. Before he did, Hudson authorized his doctors to make a public statement: “Mr. Hudson is being evaluated and treated for complications of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome.”

[Read: The day AIDS hit the fashion industry]

Hudson’s heroic public acknowledgment that he was suffering from the disease changed the national conversation around AIDS and finally put the story on the front pages of the newspapers. In the two months that followed his announcement, more than $1.8 million in private contributions were raised to support AIDS research and care for its victims.

The amount was more than twice as much as had been collected in all of 1984. The government stepped up as well. A few weeks after Hudson’s death, Congress doubled the amount of federal spending dedicated to finding a cure. “It was commonly accepted now, among the people who had understood the threat for many years, that there were two clear phases to the disease in the United States: there was AIDS before Rock Hudson and AIDS after,” Shilts wrote. “The fact that a movie star’s diagnosis could make such a huge difference was itself a tribute to the power the news media exerted in the latter portion of the twentieth century.” Shilts himself died of AIDS in 1994, at the age of 42.

After Hudson died, the president began asking his White House physician to explain more about AIDS to him. Inside the West Wing, however, there was strong resistance to growing public calls for the Reagan administration to become more aggressive in combatting the disease. Some of the president’s more conservative advisers contended that AIDS should be viewed as the consequence of moral decay rather than as a health issue. White House Communications Director Pat Buchanan, before joining the administration, had written a column in which he sneered, “The poor homosexuals—they have declared war upon nature, and now nature is exacting an awful retribution.” Many of Reagan’s allies on the right were more concerned with identifying and isolating those who had AIDS than treating and caring for them. In 1986, the conservative lion William F. Buckley, the Reagans’ longtime friend, proposed tattooing HIV-positive people—on the upper forearm if they were IV drug users and the buttocks if they were homosexual.

As the White House tried to keep AIDS at arm’s length, the effects of the epidemic were being felt close at hand. After Deaver left the president’s staff, he dispatched a young Floridian named Robert Higdon to assist Nancy and help organize a foundation to build a future presidential library. As a kid barely out of college, “I was scared to death of her at first. Everybody said she was like the dragon lady,” Higdon said. However, the two of them clicked, and Higdon became Nancy’s go-to person when she needed something done discreetly. For instance, he was the one who made the quiet arrangements for her to have a face-lift in New York in 1986 and to recuperate away from public view in the apartment of her close friend Gloria Vanderbilt.

But Higdon was suffering a private agony that he could not bring himself to share even with her. His partner, a prominent Washington real-estate developer, was dying of AIDS. “I lived two years with it in secrecy, and worked in the White House,” Higdon told me more than three decades later. He started to cry at the painful memory. “I thought, Here I work for the president of the United States, and I can’t keep my partner alive,” Higdon said. “I have all the power in the world right in front of me. What can I do? Nothing.”

Reagan’s first significant initiative against the disease came in February 1986, when he declared combatting AIDS to be “one of our highest public-health priorities” and asked Surgeon General C. Everett Koop to prepare a major report on it. Critics noted, however, that on the same day, the administration submitted a budget that called for sharply reducing federal spending on AIDS research and care programs.

Koop, an imposing figure who wore an admiral’s uniform and an Amish-style square-cut gray beard without a mustache, was an unlikely champion of AIDS activists. He was a deeply religious Presbyterian and anti-abortion crusader deemed “Dr. Unqualified” in a New York Times editorial when he was nominated in 1981. His expertise was in pediatric surgery, not public health. Initially, he put most of his effort as surgeon general into raising awareness of the dangers of smoking.

But once he was tasked to write the report, Koop undertook a full-scale effort to discover everything that could be known about AIDS. As it happened, his personal physician was Fauci, then the director of NIAID. “He would come in, he would sit down right on the couch, and he would say, ‘Tell me about this.’ So, for weeks and weeks, I started to tell him all about the things we were doing,” Fauci recalled. “Then he started going out and learning himself. So, as we were getting into the second term, and he realized this was a big problem, he shifted his emphasis from tobacco to HIV.”

[Read: How a deeply religious surgeon general taught a nation about HIV]

Koop wrote his 36-page report on AIDS at a stand-up desk in the basement of his home on the NIH campus. He did not submit it for review by Reagan-administration policy advisers because he knew that the White House would have watered down its conclusions and recommendations. Released on October 22, 1986, it was a bombshell, projecting that 270,000 Americans would contract the disease by 1991 and that 179,000 would die of it. The report used explicit language, explaining that AIDS was transmitted through “semen and vaginal fluids” and during “oral, anal, and vaginal intercourse.” A version was ultimately sent to every one of the 107 million households in the country, the largest mass mailing in American history. It carried a message from Koop: “Some of the issues involved in this brochure may not be things you are used to discussing openly. I can easily understand that. But now you must discuss them.”

Conservatives liked some of what was in the report. It warned against “freewheeling casual sex” and asserted that the surest means of preventing AIDS were through abstinence and monogamy. But they weren’t so happy with Koop’s recommendation that condoms be used as a fallback. And they were especially disturbed by his call for schools to begin educating children as young as third grade about the disease. Reagan himself was uncomfortable with the implications. “Recognizing that there are those who are not going to abstain, all right. Then you can touch on the other things that are being done,” he said in an April 29, 1987, interview with a group of reporters. “But I would think that sex education should begin with the moral ramifications, that it is not just a physical activity that doesn’t have any moral connotation.”

Meanwhile, the administration’s internal differences over AIDS started playing out in public. Secretary of Education William J. Bennett, who was a voice of Christian conservatives in the Reagan Cabinet, publicly called for mandatory AIDS testing for hospital patients, prison inmates, immigrants, and couples getting married. Koop, expressing the opinion of most medical experts, warned that such a dictate would be counterproductive, because it would foster discrimination and drive victims of the disease—many of whom already lived at the edges of society—further underground.

Disagreements within the Reagan family also became more open. In July 1987, Ron appeared in a television commercial in which he criticized his father’s administration for its lack of action. “The U.S. government isn’t moving fast enough to stop the spread of AIDS. Write to your congressman,” Ron said, and then added with a grin, “or to someone higher up.” In interviews, the president’s son took aim at Bennett in particular, saying that in calling for widespread AIDS testing, his father’s Cabinet secretary was pandering to the right-wing view that the disease was a punishment for homosexuality. Ron also appeared in a 30-minute privately funded AIDS-education film, which aired on PBS. In it, he held up a condom and spermicide and urged, “Get them and learn how to use them.”

The president was annoyed with his outspoken son. Reagan made it clear in one diary entry that his own views aligned more with Bennett’s. Ron, he wrote on July 18, 1987, “can be stubborn on a couple of issues & won’t listen to anyone’s argument. Bill volunteered to have a talk with him. I hope it can be worked out.”

Behind the scenes, Nancy had also been pushing her husband to shift his stance on AIDS. She wanted him to start by speaking out more forcefully about it. The opportunity presented itself when the screen legend Elizabeth Taylor, whom Nancy had known since their days together at MGM, asked Reagan to give the keynote address at a fundraising dinner for the American Foundation for AIDS Research, or amfAR, a leading organization of which Taylor was the national chairperson. The event was to be held in Washington on May 31, 1987, the night before what would be the largest scientific meeting held on the subject of AIDS. At the bottom of her letter, Taylor scribbled a note: “P.S. My love to you, Nancy, I hope to see you soon. E.”

Reagan accepted the invitation, no doubt at Nancy’s urging. But the first lady did not trust the White House communications shop to strike the right note in drafting what the president would say. She knew that her husband would be speaking to a skeptical—in fact, downright hostile—audience. So Nancy recruited her favorite outside speechwriter, Landon Parvin, who had left the White House in 1983, to come back and craft the address.

Parvin soon discovered that the president had never held a meeting with Koop about AIDS and, in fact, had little contact at all with the surgeon general. He called Nancy, who set up a session where the two of them could talk. But instead of the tête-à-tête that Parvin had hoped for, it turned into a much larger group, which included Bennett and Domestic Policy Adviser Gary Bauer. “The White House staff had arranged to load it with conservatives, so that Koop couldn’t get the president too much to himself,” Parvin said.

The unsurprising result was a fierce argument over what the president should say. Parvin’s notes indicate that Koop wanted Reagan to tamp down unwarranted and stigmatizing fears about the disease. He urged the president to make it clear that people could not get AIDS from swimming pools, telephones, mosquitoes, or food prepared by someone infected with HIV. One person in the room objected that “the jury is still out” on secondary means of transmitting the disease. As the discussion began spiraling out of control, Parvin decided to play his ace card. “Mrs. Reagan wants it this way,” he said.

[Read: How Nancy Reagan changed her husband’s mind on guns]

Files in the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library give an indication of how the conservative forces tried to dig in as the date for the speech grew near. Three days before, White House officials were asked for their responses to the latest draft. Robert Sweet, a senior member of the Domestic Policy Council, returned his copy with a note: “I have very serious concerns about the tone of this speech as it is written. It does not reflect the president’s deep sense of moral justice. I strongly urge major revision.” Sweet crossed out language that said victims of the disease should not be blamed, and wrote in the margin, “Homosexuals and drug users choose their lifestyle—it’s the innocent children, hemophiliacs, and unsuspecting spouses who are the victims.” None of the revisions he wanted were made.

The amfAR dinner was held in a tent outside a restaurant along the Potomac River. Hundreds of people, some of whom had AIDS, gathered outside, holding lit candles in memory of those who had already died of the disease. Reagan’s speech was repeatedly interrupted by catcalls and hissing. The audience booed when the president announced that AIDS would be added to the list of contagious diseases for which immigrants and others seeking to enter the country permanently could be denied entry. The noise grew louder as he called for “routine” testing of federal prisoners, immigrants, and marriage-license applicants. And although the president lamented the plight of some groups susceptible to HIV—hemophiliacs, spouses of IV drug users, blood-transfusion recipients, babies of infected women—nowhere in the speech did he mention the words gay or homosexual.

The audience didn’t know how much worse the speech could have been. It could also have been better, Parvin told me more than 30 years later. “There was good stuff in it, but not enough,” Parvin said. The speechwriter reproached himself for the deletion of a passage about Ryan White, a teen who had been infected with HIV from a 1984 blood transfusion and was subsequently ostracized in his hometown of Kokomo, Indiana. White rallied for the right to attend school and, in doing so, raised awareness of the need to end prejudice and ignorance around the disease. “I was fighting so many big battles that I caved on that one and didn’t mention him. I still regret that I didn’t fight that one,” Parvin said.

White died in April 1990, just weeks before his high-school graduation; four months later, Congress passed its largest-ever measure to provide assistance to people suffering from AIDS and named the law in his honor. Not until the final weeks of White’s life did Reagan meet with the boy, and by then, the 40th president was a private citizen.

Belated as it was, the amfAR speech did mark a turning point for both Ronald and Nancy Reagan. They finally began drawing the spotlight that followed them to the plight of AIDS victims and the stigma they faced. In July, not quite two months after his amfAR address, Reagan visited the National Cancer Institute’s pediatric ward and held a 14-month-old baby infected with HIV. The photo made the front page of the next day’s New York Times. In May 1988, Nancy became the honorary chairperson of the first international event at the United Nations for children affected by AIDS. To help publicize and raise money for it, Nancy invited 11-year-old Celeste Carrion, who at the time was the oldest known surviving child born with AIDS, to the White House.

[Read: How U.S. AIDS policy left a lingering epidemic]

In late June 1987, Reagan also signed an executive order creating the President’s Commission on the HIV Epidemic to investigate and recommend measures that federal, state, and local governments should take in response to the crisis. In its early months, the 13-member panel nearly collapsed because of poor leadership and internal feuding, before being put under the more able leadership of the retired Admiral James D. Watkins. The commission was also criticized for being packed with conservatives whose views did not conform with mainstream scientific thinking about the disease. Nancy waged a battle with the adviser Gary Bauer over her insistence that the commission include an openly gay member, and won. Frank Lilly, the chairperson of the genetics department at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and a board member of the advocacy and service organization Gay Men’s Health Crisis, was named to the panel.

Lilly’s appointment caused a sensation. Senator Gordon Humphrey, a Republican from New Hampshire, complained that the administration “should strive at all costs to avoid sending the message to society—especially to impressionable youth—that homosexuality is simply an alternative lifestyle.” Lilly himself put out a statement that said, in part, “As far as I know, I am probably among the first openly gay persons to have been appointed to a significant position in any U.S. administration.” There was little doubt in Washington circles how he had gotten there. An unnamed administration official told The New York Times that Lilly was on the commission “because the first lady said so.”

A draft of the commission’s final report was due in mid-1988, in the waning months of Reagan’s presidency. Expectations were that it would blame the federal government for a lack of leadership on AIDS, set out a battle plan for fighting the disease, and call for antidiscrimination legislation. All of which meant that it was likely to be ignored and buried by the Reagan administration’s top policy makers. The week before the report came out, Nancy got a call from one of their family friends, Doug Wick. He asked if he could bring someone by to meet the Reagans.

The woman he wanted the Reagans to talk with was the former museum director Elizabeth Glaser, the wife of Paul Michael Glaser, a star known to millions of television fans as Detective Dave Starsky on the late-1970s police drama Starsky & Hutch. Elizabeth, the best friend of Wick’s wife, Lucy Fisher, had a secret known only to those closest to her: Near the end of her first pregnancy, in 1981, she had started hemorrhaging. Her daughter, Ariel, was delivered safely, but Elizabeth’s bleeding wouldn’t stop, so doctors gave the new mother a transfusion of seven pints of blood. Four years later, Ariel started getting sick; lab work showed that it was AIDS. Elizabeth had been infected by the transfusion of HIV-tainted blood. Ariel had gotten the disease from her mother’s breast milk.

That mother and daughter had the disease was just the beginning of the horror. Further testing showed that Ariel’s younger brother, Jake, born in 1984, was also HIV-positive. Jake had contracted the virus in utero. At the time, there was nothing to do for children in that situation. What drugs were available had not been tested or approved for pediatric use. The Glasers’ bright, curious daughter was getting sicker and sicker; they pulled Ariel out of nursery school, knowing that she would be shunned there, and when they told the parents of her playmates, some dropped out of sight.

[Read: America moved on from its gay-rights moment—and left a legal mess behind]

One day Glaser sat at her kitchen table and made a list of people she felt needed to hear her story. Among the names she wrote down was that of Ronald Reagan. She first broached the idea with Wick over lunch. “Think about it this way,” she told him. “I’m a white heterosexual woman from their socioeconomic class and from Hollywood. Many people still think of AIDS as God’s punishment for homosexuals. Even if the president doesn’t believe that, there are still many political people who are not paying any attention to the epidemic. Maybe, just maybe, I can help change their views.”

When Wick approached Nancy, the first lady told him to bring Glaser to the residence that weekend, which was two days before the commission’s report was to be released. Nancy arranged things so that Elizabeth would have the president’s undivided attention. Coffee and sandwiches had been set out. Nancy, Wick could tell, wanted to make sure that the meeting would take place in a comfortable, intimate setting.

After they all sat down, Glaser poured out the story of the past seven years. Both Reagans had tears in their eyes as she described how Ariel, after months of being unable to walk or talk, had recently opened her eyes and said, “Good morning, Mom. I love you.” Ariel would die seven weeks later, at the age of 7.

That day in the White House, Nancy, with her customary directness, turned the conversation in a direction that Glaser hadn’t anticipated.

“How is it for your husband?” the first lady asked.

“It’s horrible,” Glaser answered. “It has been very difficult for Paul, but he has been remarkable. He is our hero, and he has stood by us.”

Nancy pressed: “What is your relationship with him?”

Glaser suddenly began to understand what Nancy was getting at. She was startled. This, after all, was an administration that didn’t even want to talk about condoms. But she sensed that Nancy was asking out of genuine sympathy. Glaser told her that, yes, she and Paul continued to have a sexual relationship, taking all the precautions her doctors had recommended, and added: “My husband kisses me and touches me, and he is really quite wonderful.”

A meeting that was supposed to have lasted for 20 minutes stretched into an hour. As Glaser and Wick were getting ready to leave, the president’s eyes locked with the distraught mother’s.

“Tell me what you want me to do,” Reagan said.

“I want you to be a leader in the struggle against AIDS, so that my children, and all children, can go to school and continue to live valuable lives; so that no one with AIDS need worry about discrimination,” Glaser replied. “Secondly, you have commissioned a report on the epidemic that’s been written by a phenomenal man. I ask you to pay attention to that report.”

Reagan responded, “I promise you that I will read that report with different eyes than I would have before.”

The Watkins Commission’s report, released on June 27, 1988, was unsparing, starting with its contention that there had been a “distinct lack of leadership” from the federal government. “It was a stunning repudiation of just about every aspect of the Reagan administration’s handling of AIDS, as well as a sweeping battle plan for how the nation might cope with the epidemic in coming years,” Randy Shilts wrote. Among its 579 specific recommendations was a call for the administration to drop its opposition to laws that would prevent discrimination against people who carry HIV; an increase of $3 billion a year in funding for the fight against AIDS at the federal, state, and local levels; comprehensive education about the disease, starting in kindergarten; and a new public-health emergency-response system, giving the surgeon general broad powers.

[Read: When an HIV crisis trumps ideology on drug policy]

Despite his assurances to Elizabeth Glaser, Reagan took only modest actions in response to the report and ignored its central recommendations. “Time went by, and nothing happened. It was almost unimaginable, but the White House took the report and put it on the shelf. Hope for thousands of Americans and people around the world sat gathering dust in some forgotten corner of some forgotten room,” Glaser wrote later. Glaser had learned on her trip to Washington that her story could move people. But that meant she had to sacrifice her privacy—and that of her two HIV-positive children—to get it out. After Ariel died, Elizabeth and a group of friends started the Pediatric AIDS Foundation, which went to work putting millions of dollars in the hands of researchers more quickly than the government seemed capable of doing. Around that time, she and her husband got word that the National Enquirer was working on a story that would reveal their family’s situation; the couple decided to step forward ahead of it, granting an interview to the Los Angeles Times that was published on Friday, August 25, 1989.

By then, Reagan was out of office and living in Los Angeles. He saw the story and called Janet Huck, the reporter who wrote it, to ask for Elizabeth Glaser’s number. Her phone rang on Sunday morning. Reagan told her how sorry he was to hear about Ariel’s death, asked whether there was anything he could do, and promised to set up a meeting with his staff. Shortly after she hung up, the phone rang again. It was the ex-president, calling back because Nancy wanted to talk with her.

“Nancy was extremely compassionate and told me how saddened she was by Ari’s death,” Glaser wrote in her memoir. “She said she knew from her own experience with breast cancer how hard it was to go through an illness in public. But she said as difficult as it is, it can do a great deal of good. She was astounded by the number of women who wrote to say that they went in for mammograms after her mastectomy.” Two days later, Glaser was in Reagan’s suite of offices in the Century City section of Los Angeles, meeting with Mark Weinberg, the former White House press aide who had led communications for the ex-president’s office. He said Reagan was eager to cut a public-service announcement. In the 1990 spot, Reagan offered what sounded like a note of regret. “I’m not asking you to send money. I’m asking you for something more important: your understanding. Maybe it’s time we all learned something new.”

In 1992, Glaser addressed the Democratic National Convention in New York that nominated Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton as the party’s candidate to take on then-President George H. W. Bush. At that point, her foundation had raised $13 million, much of which went to what it called the Ariel Project, seeking ways to prevent the transmission of AIDS from mother to child. Glaser lamented the death four years earlier of her daughter, who she said “did not survive the Reagan administration. I am here because my son and I may not survive four more years of leaders who say they care but do nothing.”

It was a fair criticism, delivered in a powerful speech. Nancy felt “a little betrayed, a little hurt, because they had come forward for her personally, and by then, they had kind of a personal relationship with her,” said Wick, who had arranged that first meeting back in 1988. “But Elizabeth felt she was fighting for her kid’s life, so pleasantries didn’t really matter.”

[Elton John: We can’t end AIDS without fighting racism]

Glaser died on December 3, 1994, at the age of 47. Her HIV-positive son, Jake, survived, and with the help of breakthrough medicines, became a healthy adult.

AIDS activists sensed a disturbing undercurrent in the Reagans’ belated involvement in their cause, a subtle message that some of its victims were more worthy of sympathy than others. Barry Krost, an openly gay Hollywood producer and manager, had been among the earliest and most prolific fundraisers for AIDS charities. After Reagan left office, Krost occasionally crossed paths with Nancy. “The first time was with a group of ladies. They were her friends. They called them the ‘Kitchen Cabinet’ or something like that,” he said. “They were trying to raise money for an event in Washington, and they kept mentioning the ‘innocent’ victims of AIDS, and after about the 10th time—do remember, I was young and a bit more irritating than I am now—I just said to them, ‘Well, this is confusing me, because I frankly don’t know who the guilty ones are,’ and I left.”

Later, however, Krost had another encounter with Nancy in Los Angeles. He was leaving Le Dome, a fashionable restaurant on Sunset Boulevard, when he spotted the former first lady dining with a mutual friend, Barbara Davis, the wife of the billionaire oilman and movie-studio owner Marvin Davis. “Barbara says hello to me and introduces me to Mrs. Reagan. I don’t do that boring thing, ‘Oh, we’ve met.’ I assume she’s met a million people. I say, ‘It’s a pleasure to meet you,’” Krost recalled. “And she just looked at me and said, ‘It’s a pleasure to see you. We owe you an apology.’” Nancy didn’t add anything further, he said. “She didn’t have to. I just said, ‘Thank you.’

“Look,” Krost added, “she ended up living a remarkable life and being a remarkable person. And I think, in the end, she did good.” Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that she tried to. But when it mattered the most, while her husband was still in office, Nancy might have spoken up publicly. She might have pushed harder to jolt the president of the United States out of his passivity. Almost 83,000 cases of AIDS were confirmed while Reagan was in the White House. Nearly 50,000 people died of the disease. Those numbers—those lives cut short—are a part of his legacy that can never be erased.