Harness the power of your circadian rhythms for weight loss by making breakfast or lunch your main meal of the day.

In my last chronobiology video, we learned that calories eaten at breakfast are significantly less fattening than the same number of calories eaten at dinner, as you can see at 0:14 in my video Breakfast Like a King, Lunch Like a Prince, Dinner Like a Pauper, but who eats just one meal a day?

What about simply shifting our daily distribution of calories to earlier in the day? Israeli researchers randomized overweight and obese women into one of two isocaloric groups, meaning each group was given the same number of total calories. One group got a 700-calorie breakfast, a 500-calorie lunch, and a 200-calorie dinner, and the other group got the opposite—200 calories for breakfast, 500 for lunch, and 700 for dinner. Since all of the study participants were eating the same number of calories overall, the king-prince-pauper group should have lost the same amount of weight as the pauper-prince-king group, right? But, no. As you can see in the graph below and at 1:01 in my video, the bigger breakfast group lost more than twice as much weight, in addition to slimming about an extra two inches off their waistline. By the end of the 12-week study, the king-prince-pauper group lost 11 more pounds than the bigger dinner group, dropping 19 pounds compared to only 8 pounds lost by the pauper-prince-king group—despite eating the same number of calories. That’s the power of chronobiology, the power of our circadian rhythm.

What was the caloric distribution of the king-prince-pauper group getting 700 calories at breakfast, 500 at lunch, and 200 at dinner? They got 50 percent of calories at breakfast, 36 percent at lunch, and only 14 percent of calories at dinner, which is pretty skewed. What about 20 percent for dinner instead? A 50% – 30% – 20% spread, compared to 20% – 30% – 50%?

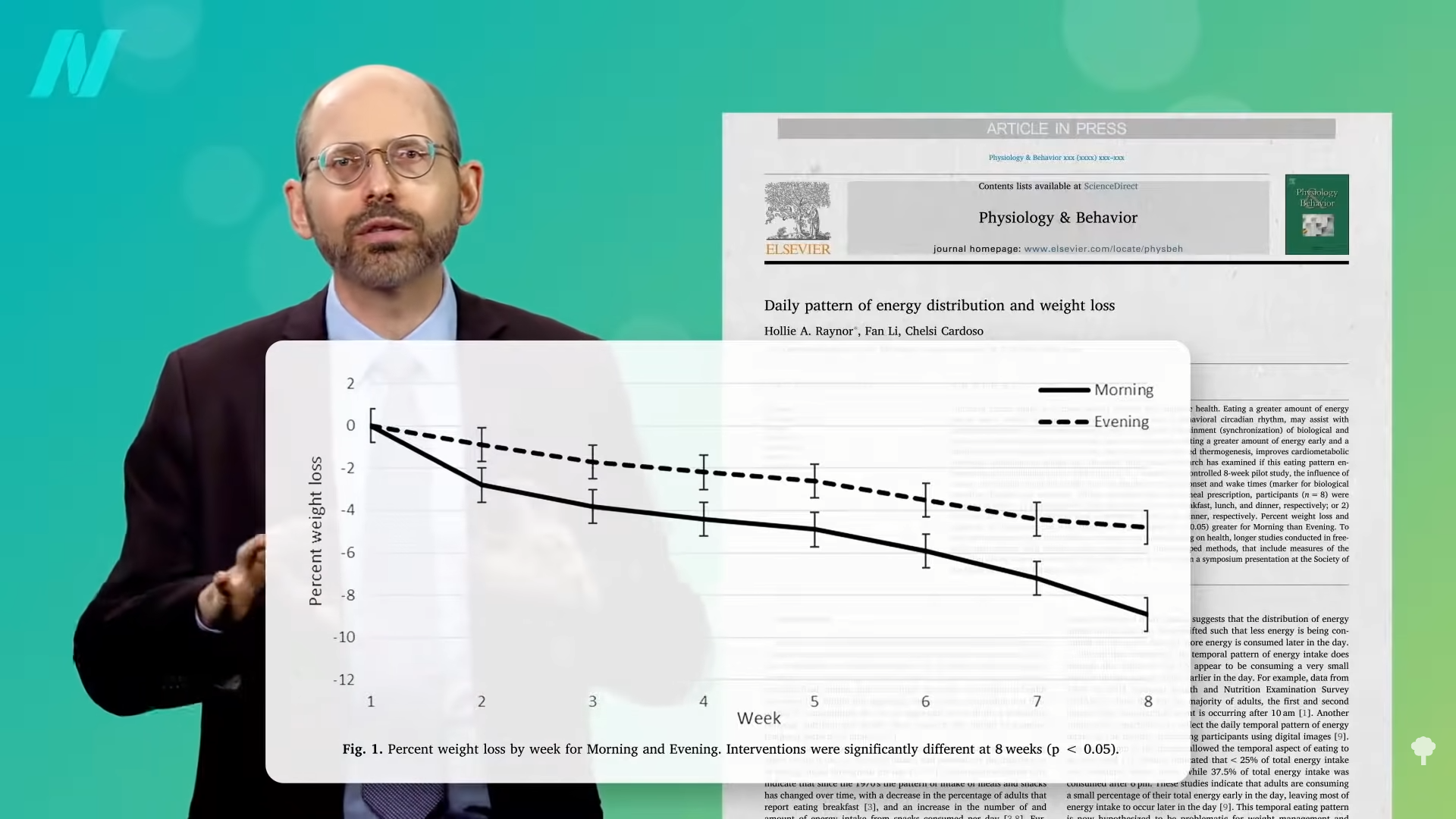

Again, the bigger breakfast group experienced “dramatically increased” weight loss, a difference of about nine pounds in eight weeks with no significant difference in overall caloric intake or physical activity between the groups, as shown in the graph below and at 1:57 in my video.

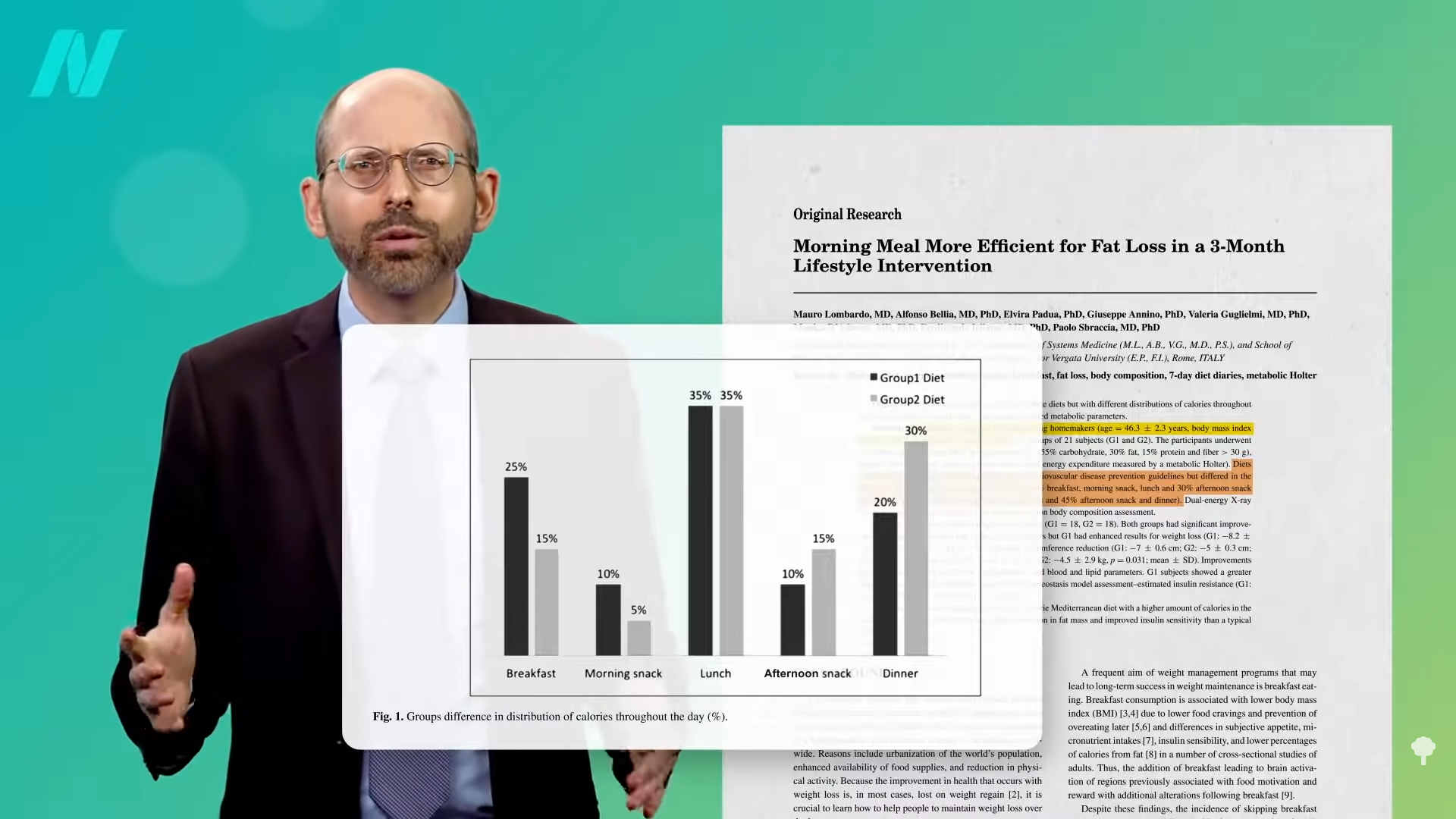

Instead of 80 percent of calories consumed at breakfast and lunch, what about 70 percent compared to 55 percent? Researchers randomized overweight “homemakers” to eat 70 percent of their calories at breakfast, a morning snack, and lunch, leaving 30 percent for an afternoon snack and dinner, or a more balanced 55 percent from the time they woke up through lunch. In both cases, only a minority of calories were eaten for dinner, as you can see below, and at 2:25 in my video. Was there any difference between eating 70 percent of calories through lunch versus only 55 percent? Yes, those eating more calories earlier in the day had significantly more weight loss and slimming.

Concluded the researchers: “Stories about food and nutrition are in the news on an almost daily basis, but information can sometimes be confusing and contradictory. Clear messages should be proposed to reach the greatest number of people. One clear communication from physicians could be ‘If you want to lose weight, eat more in the morning than in the evening.’”

Even just telling people to eat their main meal at lunch rather than dinner may help. Despite comparable caloric intakes, participants in a weight-loss program randomized to get advice to make lunch their main meal beat out those who instead were told to make dinner their main meal.

The proverb “Eat breakfast like a king, lunch like a prince, and dinner like a pauper” evidently has another variant: “Eat breakfast yourself, share lunch with a friend, and give dinner away to your enemy.” I wouldn’t go that far, but there does appear to be a metabolic benefit to frontloading the bulk of your calories earlier in the day.

The evidence isn’t completely consistent, though. A review of dietary pattern studies questioned whether reducing evening intake would facilitate weight loss, citing a study that showed the evening-weighted group did better than the heavy-morning-meal group. Perhaps that was because the morning meal group was given “chocolate, cookies, cake, ice cream, chocolate mousse or donuts” for breakfast. So, chronobiology can be trumped by a junk-food methodology. Overall, the what is still more important than the when. Caloric timing may be used to accelerate weight loss, but it doesn’t substitute for a healthy diet. When he said there was a time for every purpose under heaven, Ecclesiastes probably wasn’t talking about donuts.

When I heard about this, what I wanted to know was how. Why does our body store less food as fat in the morning? I explore the mechanism in my next video, Eat More Calories in the Morning Than the Evening.

This is the fifth video in an 11-part series on chronobiology. If you missed the first four, check out the related posts below.