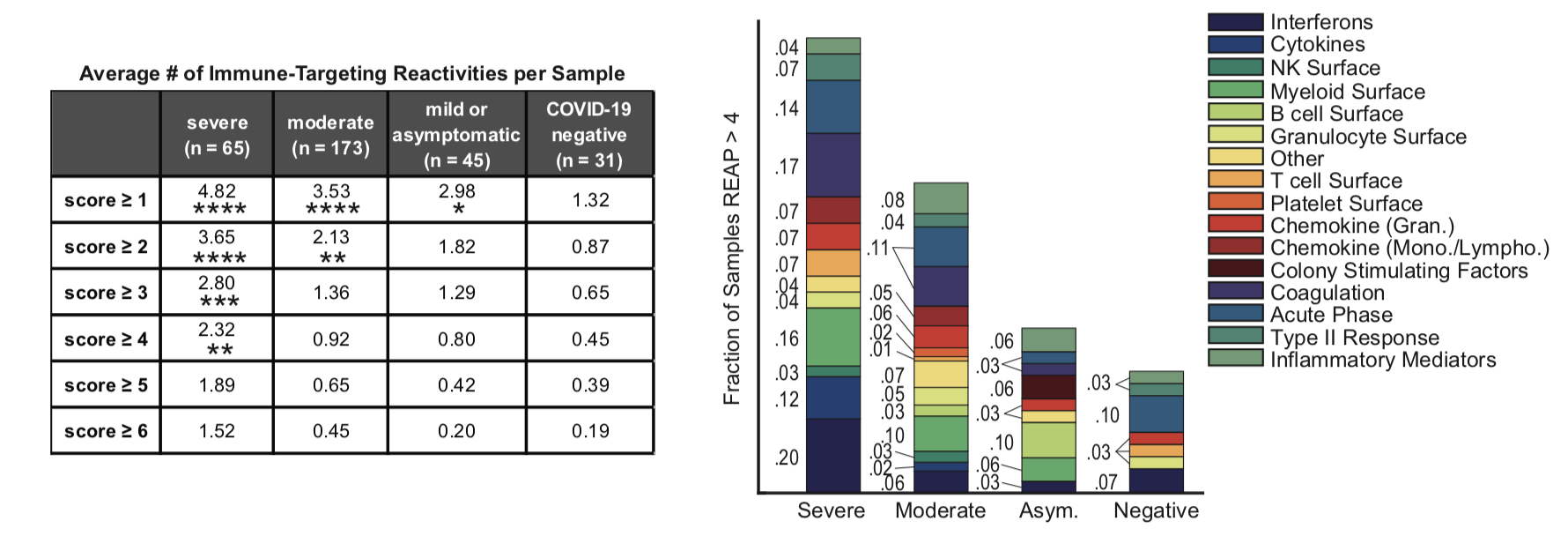

And it looks like one of those details, potentially a very important one, is a striking correlation with autoantibodies. Those are antibodies to a person’s own proteins – the sort of friendly fire that you see in autoimmune diseases of all sorts (acute and chronic). This work features a new assay (Rapid Extracellular Antigen Profiling, REAP) against a displayed library of 2,770 extracellular (secreted) human proteins displayed via yeast cells, providing a high-throughput method to check a patient’s own serum for antibodies to these. 194 subjects (Yale patients and healthcare workers) were screened, with a wide range of disease severity, as compared to 30 uninfected controls. The new assay showed good correlation with standard ELISA assays as a reality check.

It appears that the more severe a coronavirus infection a patient has, the better the chances that they show a wide variety of autoantibodies towards their own cell-surface and secreted proteins (see the figures above). I wrote here about a study that showed that patients with antibodies towards some of their own interferons have a harder clinical course of the disease, and this new paper confirms that work and extends it. A set of patients were examined over time, and it appears that at least 50% of these reactivities were observed early enough in the course of the disease that they may well have been pre-existing. Around 10% of them were seen to increase over time, though, suggesting that the coronavirus infection was bringing on such autoimmune problems. Interestingly, about 15% of the antibody titers seemed to decrease over time, and I’m not sure what to make of that.

The paper goes on to make connections between specific autoantibodies and immune function – for example, some of the ones that target specific proteins on the surfaces of immune cells are associated in patients with decreased numbers of those cells. The team also looked for correlations between antibodies to specific targets (or those associated with specific tissues) and clinical outcomes. It’s a complex thing to untangle, though. If you think about some specific circulating cytokine protein, antibodies to it could help to clear it from the bloodstream more quickly, or to bind to it in a way that keeps it from working (either partially or completely, which seems to be the case for the interferon autoantibodies), or at the other end of the scale, to bind to it in a way that doesn’t interfere so much with its function and could even stabilize its levels in the blood.

But overall, there was no well-defined set of “COVID-19” antibodies that showed up in infected patients but not in controls, and no obvious ways to match up antibody profiles to specific outcomes. Some of that difficulty, though, may be due to the wide variety of responses seen. Instead of broadly obvious trends, what shows up are a great number of individual responses that can add up to real outcomes, but which are very hard to untangle. Immunology!

One of the things that needs to be done, then, is more extensive profiling in the population. I would assume that ideally you’d want to get a good-sized sample of healthy people, profile them for autoantibodies, and then watch over time to see what happens. This isn’t just a coronavirus story at that point. Are there people who have greater susceptibility to various diseases, or to worse outcomes, if they have particular autoimmune fingerprints? Or will it still be a big tangled ball of yarn if you try to track these things down? At the least, I would expect that if there is indeed a population who have some sort of partial failure of immune tolerance and thus show existing high levels of auto-antibodies, they they would be at greater risk of severe coronavirus infection. How many such people are there, and how many of them are currently unrecognized?

Beyond that, there’s the possibility that some of the autoimmune effects are being actually brought on by the infection. We already know about some of the larger, more obvious examples of this sort of thing (such as Guillain-Barré and others), but profiling via an assay like REAP could help to shed more light. There are already several mechanisms known for such tolerance failures, but it’s for sure that there’s a lot more to learn, and I would think that a good-sized longitudinal study might have a lot to tell us. (Of course, I’m not the person who has to go out and get funding for it, so that’s easy for me to say!)