It has all those numbers because it has some history behind it. The compound was discovered at Emory in the university’s Drug Innovation Ventures nonprofit spin-off, which has been working on antiviral nucleoside derivatives for many years. The compound was heading for clinical trials against influenza when the pandemic hit, and last March they did a deal with Ridgeback Biotherapeutics to accelerate its progress in coronavirus treatment. Ridgeback then partnered with Merck later in May for the clinical trials and scale-up.

The course of small-molecule antiviral drugs during the coronavirus pandemic has not been straightforward. Let’s just put it that way. Remdesivir has had a great deal of attention, and in the end seems to be somewhat useful but not exactly game-changing, and frankly it’s been the best of the bunch. Many other compounds were being talking about this time last year, but have failed to make much of an impression. A priori, though, that’s what you’d expect. In general, there aren’t that many effective antiviral drugs, and the ones we have are extremely concentrated in two areas: HIV and hepatitis C. Those in turn have been extensively, painstakingly developed against specific viral targets for those pathogens. It’s safe to say that there (so far) have been no really effective broad-spectrum antiviral small molecules.

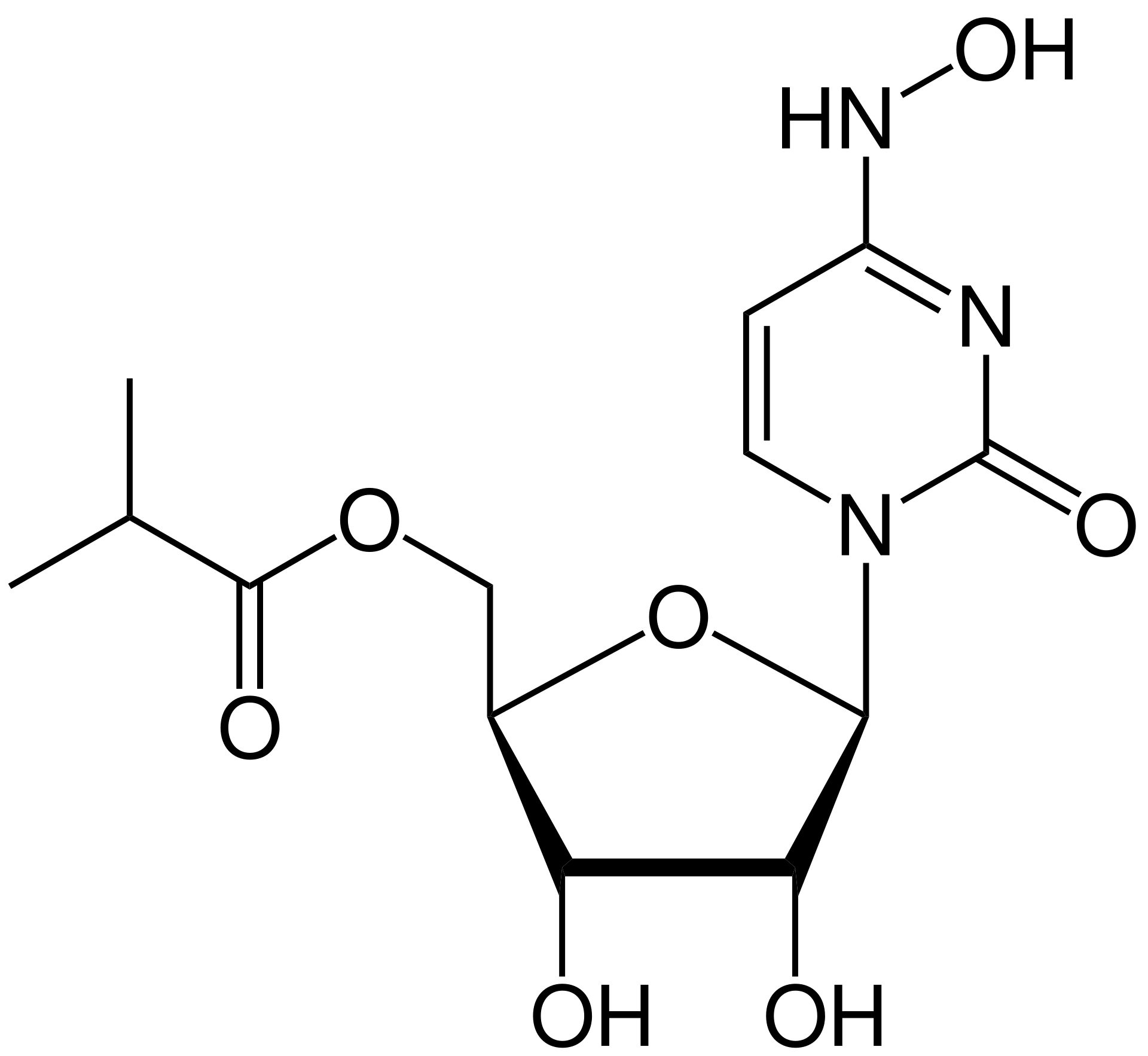

But molnupiravir is one of the best shots at that. It’s a prodrug of N4-hydroxycytidine (NHC), a nucleoside analog that’s been investigated for decades now. Like many nucleoside analogs, it has its good side and its bad side. The good side is that these compounds can cause trouble (in several ways) for viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, an absolutely critical enzyme for the replication of any RNA virus. A common mechanism is what’s called an “error catastrophe”. These enzymes are notoriously error-prone to start with, and viruses over the eons have added several mechanisms to try to keep that under control – but remember, a background mutation rate is also a survival advantage (throwing off new variants), just so long as it doesn’t get out of control. Nucleoside analogs, in many cases, work by doing just that – pushing the RNA replication step into making so many errors that the end result can’t even produce a competent virus.

That’s the effect of NHC and of molnupiravir. What about the bad side? Well, auxh nucleosides can also be taken up by many other enzymes, including those that handle our own nucleic acids, so some of them are mutagenic. Indeed, that’s how NHC was first characterized, as a mutagen in bacteria. They also tend to be cytotoxic, via a number of mechanisms, and nucleoside drug candidates are notorious for wiping out in human trials due to toxicity in the liver, kidneys, and other organs. That was a feature of the 2012 scramble in the hepatitis C area, where Bristol-Myers Squibb paid 2.5 billion for a nucleoside addition to its proposed therapeutic cocktail, only to see it all demolished within a few months when it turned out to have severe problems in human trials. From this story and others you can also conclude that you don’t necessarily get a good reading on this stuff in animal trials – another feature of Fun With Nucleosides.

Molnupiravir itself has shown strong activity against a whole list of viruses in preclinical studies – it is indeed a very interesting candidate, even more so because it seems to have an unusually high barrier to resistance mechanisms. In December, animal studies showed that it could indeed protect against coronavirus infection. But you’d still definitely classify it as “high risk, high reward”. That means that this new paper comes as something of a relief: it’s first-in-human data from the Phase I trial.

So far, so good. There were no show-stopping adverse events (in fact, adverse events in general were higher in the placebo group), and the pharmacokinetics look straightforward: dose-proportional exposure, reasonable half-life, no accumulation on repeated or increased dosing, and plasma levels that appear to match the efficacious ones seen in the animal studies. The higher planned doses in the trial were in fact discontinued due to those levels being covered, which is always a good sign. Since it’s a prodrug, with that isobutyl ester rapidly cleaved in plasma, you mostly see the N-hydroxycytidine itself in these measurements, as you’d expect (about 99.8% NHC and 0.2% parent). Interestingly, only traces of either the parent or NHC show up in the urine, although elimination through the kidneys is a common route with nucleoside analogs. It appears that the NHC is getting pretty completely metabolized to cytidine and/or uridine (which would not be a bad profile, either, since those are common biomolecules that are soaking through every living tissue already).

The key, though, will be finding out if the compound is any good against the coronavirus in humans. And those trials have been underway for a while, with the latest news being that we might hear results this quarter. Which means by the end of this month? We’ll see – I hope that the news is good, because the world could use an orally delivered small molecule coronavirus drug, and it could also use a new antiviral in general (which this one, as mentioned, has a real chance to be).

Take a moment to think about the flip side of all this, though: here’s a known compound, already investigated against a number of viruses (in vitro and in animal models), with a promising mechanism of action that gave some confidence that it would have activity against a new RNA virus pathogen, and which was already heading towards human trials. You could not ask for a better-positioned small molecule; this is as good as it gets. So the time it’s taken to get the clinical read on whether it really works or not is about as fast a development as you’re going to see. Everything was lined up perfectly and a lot of the work had already been done. Keep that timeline in mind as a baseline!