I wrote here about the reports of rather short antibody persistence in recovering coronavirus patients, and what’s been coming out in the two weeks since then has only made this issue more important. In that post, I was emphasizing that although we can measure antibody levels, we don’t know how well that correlates with exposure to the virus nor to later immunity from it, and that T cells are surely a big part of this picture that we don’t have much insight into.

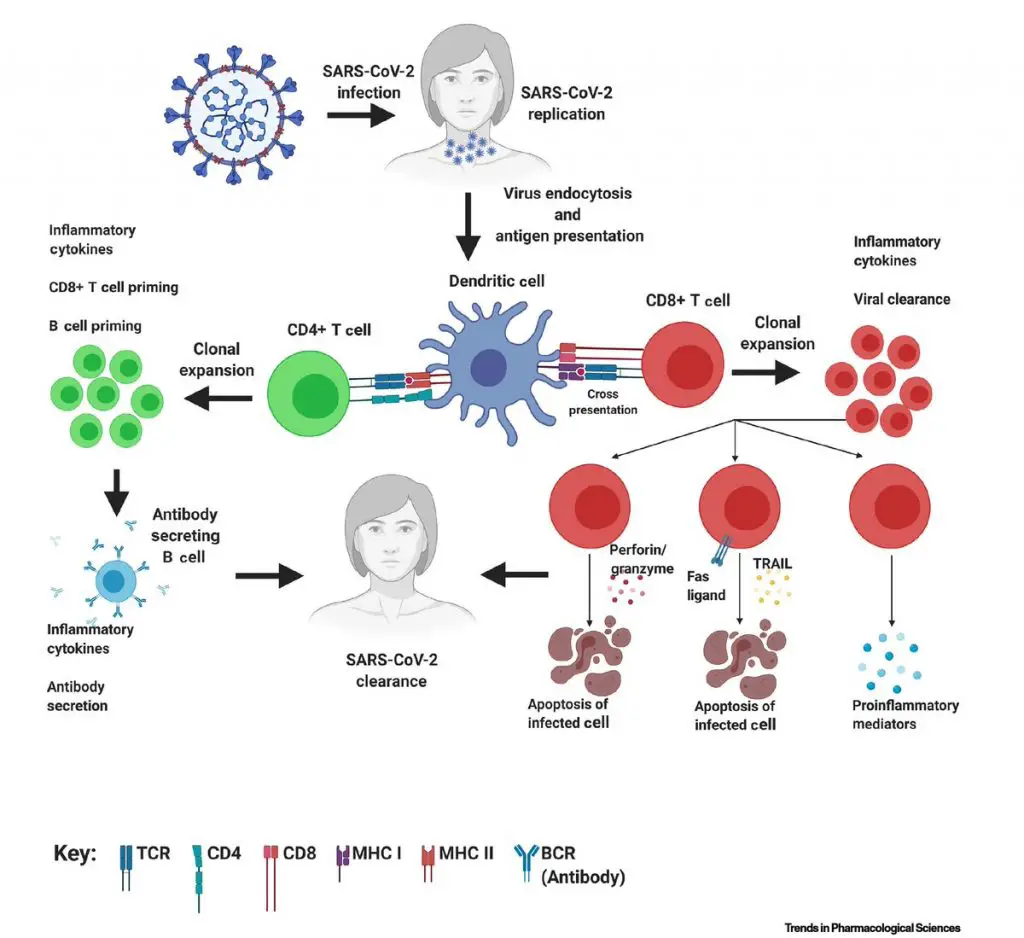

This Twitter thread by Eric Topol is exactly what I mean, and this article that he references is an important read. Its schematic at right (see also here) will help make clear that antibody levels are only one aspect of the immune response to the infection – it’s an important one, but we’re making it look even more important than it is because it’s by far the easiest part of the process to measure. The T-cell response (much harder to get good data on) is known to be a key player in viral infections, and is also known to be highly variable, both between different types of pathogens and among individuals themselves. The latter variations are also beginning to be characterized among patients in the current pandemic. We have to get more data on it across a broader population of patients in order to make sense of what we’re seeing.

Many readers will have seen, for example, this new paper from The Lancet on a large study in Spain. Testing tens of thousands of people across the country continues to show that (on average) only about 5% of the population is seropositive (that is, has antibodies to the virus). There are a lot of interesting findings – such as rather large differences in those positive testing rates in different regions of the country, as well as the realization that at least one-third of the people who now test positive never showed any symptoms at all. But we are still not sure if this means that 95% of the Spanish population has never been exposed to the virus, because we don’t know how many people might have cleared it without raising enough of an antibody response to still be detectable. This paper does show that seroprevalence was about 90% in people 14 days after a positive PCR test, which indicates that most people do raise some sort of antibody response, but we don’t know how many of these people will still show such antibodies at later testing dates. Remember the paper discussed in that link in the first paragraph above, which found that 40% of asymptomatic patients went completely seronegative during their convalescence.

In other words, the Spanish survey may appear to show that 95% of the country has not yet been exposed to the coronavirus, but that’s almost certainly not true. The authors do mention that cellular immunity is important and not something that they were able to address, but the combination of that factor plus the apparent dropoff in antibody levels with time makes these large IgG surveys almost impossible to interpret. But note that if there are indeed many people who have been exposed but do not read out in such surveys, that we also have no idea how immune they are to further infection. At a minimum, you’d want to know antibody levels over time, T-cell response over time, and (importantly) what a protective profile looks like for both of those. We barely have insight into any of this: the large-scale data are just a snapshot of antibody levels, and that’s not enough.

We have similar data here in the US: several surveys of IgG antibodies show single-digit seroconversion. You could conclude that we have large numbers of people who have never been exposed – and indeed, the recent upswing in infections in many regions argues that there are plenty of such people out there. But we need to know more. We could have people who look vulnerable but aren’t – perhaps they show no antibodies, but still have a protective T-cell response. Or we could have people who look like they might be protected, but aren’t – perhaps they showed an antibody response many weeks ago that has now declined, and they don’t have protective levels of T-cells to back them up. Across the population, you can use the limited data we have and our limited understanding of it to argue for a uselessly broad range of outcomes. Things could be better than we thought, or worse, getting better or deteriorating in front of our eyes. We just don’t know, and we have to do better at figuring it out.