First off, safety. There continue to be no serious concerns that I can see. There were two deaths in the vaccinated group, and 3 in the placebo group (both about 19,000 people). More people withdrew from the study in the placebo group. There were 18 adverse events characterized as “life-threatening” in the vaccine group after one month of follow-up, but there were 19 of those in the placebo group, and so on (for two months of follow-up, those numbers were 10 in the vaccine group and 11 in the placebo). There were four incidents of Bell’s palsy (temporary facial nerve problems) across the total participants, all four of those in the vaccine group. That’s worth keeping an eye on, but it’s about the number of people you’d expect to show it in a population that size (Bell’s palsy is not extremely rare), and thus can’t really be associated with the vaccine with that number of incidents. The events that were clearly associated with the vaccine were reactogenic ones (injection site pain, soreness, stiffness, fever, headaches, etc.) Older patients tended to have fewer of these, having overall less active immune systems. Word has come this morning that two severe immune reactions have been seen in the UK, both in National Health Service workers with long personal histories of severe immune reactions, but in general, such people are at higher risk with any vaccine. I have not gone through every line of the safety material, but so far I do not see anything in there that would be a problem for Emergency Use Authorization or later full approval.

We also have a great deal of fresh data on the immunogenicity of the vaccine, both antibody response and T-cell responses. I’m not going to try to summarize those for now because (1) everyone mostly cares about the efficacy and (2) once we have more data of this kind with other vaccines we can try to make some sort of head-to-head comparison. In the Phase I studies, this vaccine showed robust neutralizing antibody levels and T-cell responses, and those numbers look to have continued in the larger Phase 2/3 study, as expected.

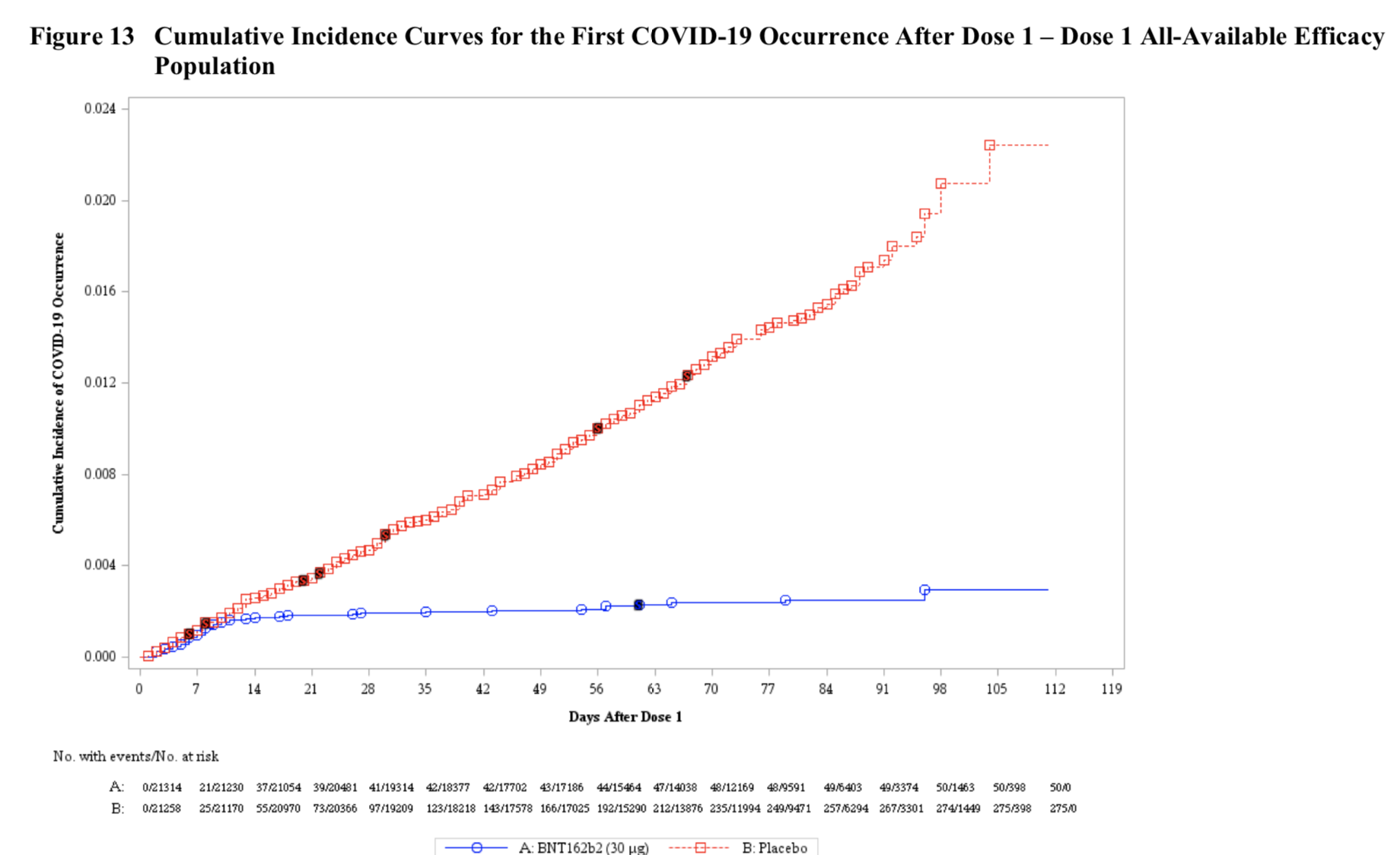

Now to efficacy. As we know, “overwhelming efficacy” was declared at the first (and only!) interim analysis, with 94 total cases split 90/4 between the placebo group and the vaccinated group. The final analysis shows 170 cases, split 162/8 (confirmed coronavirus infection at least 7 days after the second dose). That’s a VE (vaccine efficacy) of 95%, with the 95% confidence interval on that number running from 90.3% to 97.6%. A new and interesting data set cover what happened after the first dose and before the second. There were 50 cases of coronavirus in the one-dose treatment group, versus 275 in the placebo group. But look at how those 50 cases came on:

What you can see is that the great majority of those 50 cases happened in the first ten to fourteen days or so after the first shot. At that point, the vaccinated group and the controls diverge sharply, and that’s because ten to fourteen days is the time it takes to raise an antibody response after a vaccination. You can see it kicking in, right there in the chart. This vaccine, in fact, already meets the FDA’s threshold of 50% efficacy with just one shot (but has much greater efficacy, of course, with the two-shot regimen). It’s worth noting that 10 cases of severe infection developed in the treatment group after just one shot, versus only 1 such case after two shots.

Table 8 in the FDA’s document has a good look at the various subgroups in the vaccinated population, and it’s hard to see any real differences in there. Age, gender, body mass index, ethnicity, risk factors – to my eyes, there’s not much to choose from, and that’s a good thing.

So it looks like the vaccine has a very strong protective effect, and that’s the first thing you’d want to know. But there are many other things we don’t know yet. What, for example, is its effect on transmission of the disease? We should be seeing more on that early next year, but based on these figures, it seems very likely that this vaccination would cut down the transmission rate sharply. But that has to be proven; there are plenty of things that have seemed very likely over the years in drug development that haven’t worked out. Even at this point in the pandemic, we don’t have solid numbers about the correlation between just what sort of viral load a person is carrying and their infectiousness to others. Think about how you’d try to design such a study and you can see why the data are lacking! We also don’t know the effectiveness of the vaccine in preventing asymptomatic infections, because this trial was based on symptoms, not on constant PCR testing of its participants, which is the only way you’d accumulate such data. The stronger knockdown of severe cases makes one think that asymptomatic cases might be similarly decreased, but you could also imagine that you would take what would be “normal” symptomatic cases and knock them back to being real-but-asymptomatic ones. A priori, you can’t be sure what the real situation is. That question is tied up with the transmission one, of course. We also don’t know what the duration of protection is, for the very simple reason that time just has to keep on tickin’, tickin’, into the future, (S. Miller et al.) for us to have any data on that. There’s no other way; we can’t estimate these things. That we will certainly have data on – eventually.

The data that Pfizer and BioNTech have presented look like far more than would be needed for an Emergency Use Authorization. I expect the FDA to grant that, and very soon. All the concerns about the effect of one or more EUAs that I wrote about here are still real. But some of them are less troublesome now that both this vaccine and Moderna’s have read out with such high efficacies – I was most worried about the first vaccine candidate showing decent-but-not-great effects, and that fortunately has not happened. But questions about (for example) the Pfizer placebo group switching over to vaccine, about the effects of these EUAs on other vaccine trials, and so on are still with us, and are yet to be resolved.

At any rate, any EUA is going to be accompanied by a large monitoring requirement. We’re going to be collecting a lot more data on this vaccine and others as they move into larger populations, data on both safety and efficacy. Vaccine work has its unique challenges because of its unique situation of dosing huge numbers of people who aren’t sick yet, and because of its targeting of the wildly complicated, wildly variable immune system. If there is some nasty side effect that is literally at the one-in-a-million level, which given immunology is absolutely possible, we certainly would not expect to see it in a 38,000-person trial (huge though that is by clinical trial standards). But we certainly would see it after dosing a few hundred million people.

Remember, though, what an EUA is for. That word “emergency” is there for a reason: this authorization is for something extremely serious for which there is no available alternative. That’s exactly the situation we find ourselves in, on both counts, and I think that the risk/benefit ratio is clearly, overwhelmingly in favor. Let’s do it.