Yet the U.S. is still making the same two deadly mistakes that have defined its response since the pandemic began, our ongoing investigation has found. The nation still does not have enough tests to combat the pandemic. And it is still allowing the virus to rampage through nursing homes and other long-term-care facilities.

[Read: Where year two of the pandemic will take us]

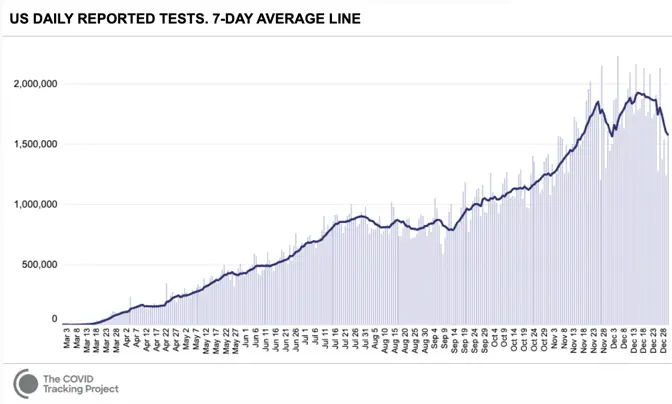

After an early failure in February left the country with growing caseloads and too few COVID-19 tests to track the outbreak, the U.S. has never caught up. By the middle of December, the country tested about 1.8 million people a day for the virus, which was close to an all-time high. But to begin fighting the virus through testing—by, for instance, identifying infected people before they pass the virus to others—the U.S. must test at least 4.4 million people a day, according to the Harvard Global Health Institute. Ideally, given the scale of the pandemic, the country would run 14 million tests a day, the institute posits.

By our count, the U.S. has conducted more than 248 million tests since the pandemic began, a staggering total. But the virus is now so widespread that if America were meeting that ideal testing target, it would run about that many tests every two and a half weeks.

The U.S. has never tested as many people as it needs to in order to keep the pandemic in check. It has gone weeks at a time—from late July to mid-September, most strikingly—without increasing the number of people tested every day. At moments when infection has been especially widespread, companies have taken days or even weeks to process test results. Federal regulators have been slow to approve rapid virus tests that could be used at home without a prescription, similar to pregnancy tests.

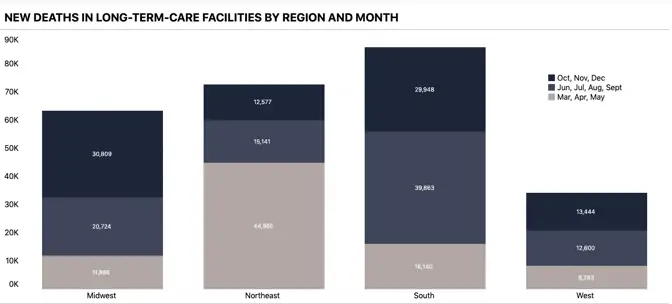

This has compounded a second crucial failure. In the spring, the country learned that the virus is deadliest in long-term-care facilities such as nursing homes. Though these facilities house less than 1 percent of America’s population, they have seen at least 38 percent of the nation’s COVID-19 deaths, our data show. (Some states report incomplete data for these facilities, meaning that this number likely undercounts the true toll originating in these settings.)

The Trump administration has claimed that saving lives at such facilities is core to its pandemic strategy. Scott Atlas, a neuroradiologist who advised Donald Trump on virus policy for much of the summer and fall, argued that there was little risk in allowing the virus to spread through the general population as long as officials focused on “protection of the vulnerable” in nursing homes.

[Read: The last days of loneliness]

Yet the country has never succeeded at protecting the vulnerable, our data show. In December alone, at least 20,455 people have died in long-term-care facilities and nursing homes, the greatest toll since the COVID Tracking Project began collecting long-term-care data in late May. And in every region of the country but the Northeast, more people died in long-term-care facilities in the summer and fall than in the spring.

These two debacles have preyed on the effectiveness of the American pandemic response from the start. At the end of the year, the U.S. has more diagnosed COVID-19 cases than any other country, and it ranks fourth worldwide in COVID-19 deaths per capita. And December has been the deadliest month of the pandemic so far, our data show. Its death toll has exceeded that of April by 29 percent.

These data were collected by the COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic. For each of the past 299 days, a team of volunteers and project members has watched press conferences, tracked social-media posts, and combed through dozens of government websites to compile the COVID-19 data that each U.S. state and territory provides. The project now records nearly 800 individual statistics.

The resulting database is a patchwork, built from the individual components that each state’s data systems capture and from the numbers that local political leaders allow to be published. Fusing together 56 state and territorial data sets can be a fraught, complex process, and the project publishes exhaustive documentation of what the numbers mean, how they compare to one another, and what we still don’t know, because of the variability of state reporting.

One of the most obvious elisions is the toll that the pandemic has taken on Black, Latino, and Indigenous people. The pandemic has disproportionately killed people in these communities, our data show. At least one in every 800 Black Americans has died of COVID-19, and Black people have died of COVID-19 at 1.7 times the rate of white people. Nationwide, Indigenous people and Alaska Natives have died of COVID-19 at 1.4 times the rate of white people.

[Read: The virus is showing Black people what they knew all along]

Yet the full scale of this damage is not quantifiable, because many states still do not track enough data by race and ethnicity for us to identify the full, disparate impact. Texas, for instance, reports race and ethnicity data for only 4 percent of cases. New York has never reported race and ethnicity data, which obscures our understanding of the first surge in particular, when New York’s numbers dominated every national statistic.

Only seven states report the racial breakdown of testing data, an important tool in detecting how large outbreaks are overall, because knowing the fraction of a population that has been tested can indicate the breadth of the virus’s spread.

Because of such inconsistencies and gaps, the COVID Tracking Project team has also communicated with state and federal officials hundreds of times over the past 10 months to clarify the meaning of specific numbers and to push for higher data quality and more public transparency.

This effort meant that, for months, the COVID Tracking Project published the only public database of testing and hospitalization data. Today, it is the only data set detailing each state’s and territory’s daily case, testing, hospitalization, and death numbers since the pandemic began. The federal government, including the White House Coronavirus Task Force, has used data from our investigation because it has had no alternative. The CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has repeatedly cited our data on long-term-care facilities in the course of deciding that residents of those places should get vaccinated first.

[Read: What the vaccine’s side effects feel like]

Today, the federal government publishes data on many of the same metrics we began tracking in March. But for many of these metrics, our data remain the only independent check on that federal data.

The COVID Tracking Project has repeatedly identified issues with the data shared at the state and federal level. For instance, in the spring the CDC made the state of the pandemic less clear by lumping together two different types of tests—antibody tests, which detect past infection, and diagnostic tests, which detect present illness. Test-positivity statistics, widely used to make decisions about pandemic restrictions, still show massive variability, we have found, which make them extremely difficult to use when setting interstate policy. Now the millions of inexpensive, rapid tests that the Trump administration purchased and directed to vulnerable populations are not being reported at either the state or federal level.

Over the past 10 months, we have seen the federal government struggle to acquire, present, and analyze the data necessary to understand the pandemic. This could change in the coming weeks: The incoming Biden administration has said that it plans to make a National Pandemic Dashboard. What will matter, then, is not only having the data, but using them to save lives.