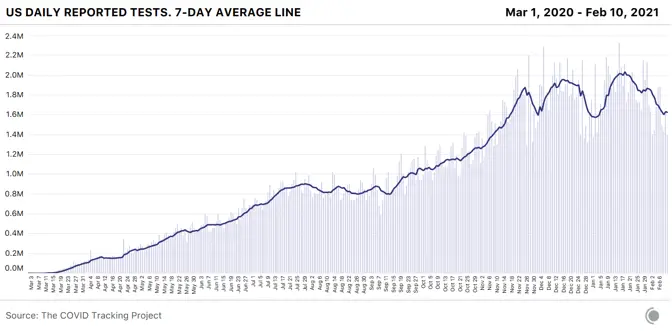

The testing decline we’re now seeing is almost certainly due to a combination of reduced demand as well as reduced availability or accessibility of testing. Demand for testing may have dropped because fewer people are sick or have been exposed to infected individuals, but also perhaps because testing isn’t being promoted as heavily.

The resolution of holiday reporting backlogs also almost certainly produced an artificial spike in the number of tests reported in early January—which means the decline we’re seeing now looks particularly dramatic when measured against that postholiday spike.

Even if we adjust for holiday effects and estimate that we’re really testing only 1 million fewer people each week than we did a month ago, that’s unequivocally the wrong direction for a country that needs to understand the movements of the virus during a slow vaccine rollout and the spread of multiple new variants.

According to public-health experts, we’re also still not doing enough testing, —and we weren’t doing enough even at the January testing peak. Back in October, the Harvard Global Health Institute and NPR released testing targets that set a national target of about 2 million PCR tests a day. If we discount holiday effects, the United States finally hit that target in the week ending January 20, when states reported about 14 million tests—though the number immediately began dropping. But the HGHI test targets were based on October 1 case counts, and even after weeks of declines, we’re seeing more than twice as many new cases a day now as in early October. Vaccinations are only one component of the effort to get the pandemic under control and prevent another devastating surge. We need to be testing at our full capacity—and increasing that capacity—to keep eyes on the pandemic as we move into spring.

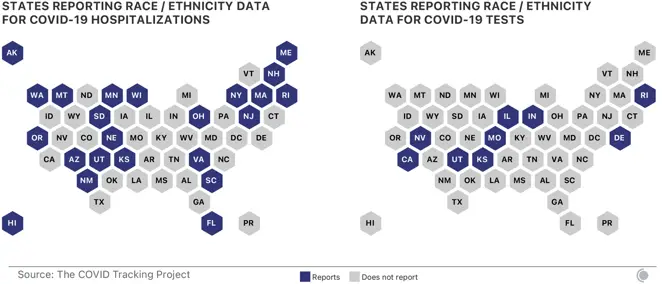

Both testing and hospitalization data are crucially important COVID-19 metrics, helping us understand how the pandemic is changing and how to interpret other data we’re collecting. The race and ethnicity data for these metrics remain deeply inadequate in both state and federal data sources. Nearly a year into the U.S. pandemic, only 23 states report or have reported any data about the race and ethnicity of people hospitalized with COVID-19, and only nine states share data about the race and ethnicity of people who receive COVID-19 tests. As Marcella Nunez-Smith, the chair of the Biden-Harris COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force, said at a Kaiser Family Foundation briefing in December 2020, “There is violence in data invisibility. We cannot address what we cannot see. We are making a choice every time we allow poor-quality data to hinder our ability to intervene on racial and ethnic inequities.”

Although media and policy attention is increasingly focused on the lack of demographic data for vaccinations—data on race and ethnicity are missing for about half of all first doses administered in the first month of the U.S. vaccine rollout, according to a CDC report—demographic data for other COVID-19 metrics remain essential for identifying inequities in either impact or response. Without good, public demographic data on hospitalizations and tests, there can be no accountability for efforts to identify and address inequities. States and the federal government should work together to ensure that hospitals and testing providers are collecting sufficient demographic data, and that these data are rapidly and publicly shared.