Standard

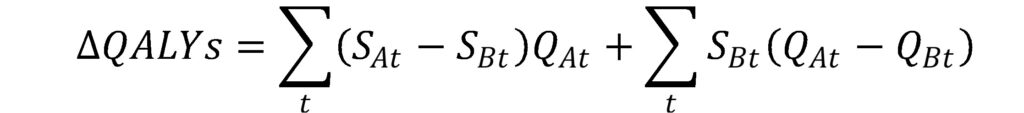

quality approach compares the difference in QALYs which is a function of survival

and quality of life during each survival period. Consider the comparison of treatments A and

B, where treatment A is the novel treatment and treatment B is the standard of

care. Under the QALY based approach this is calculated as

Where the

S term is the survival probability in a given year and the Q term is the

quality of life in that year. One can add and subtract a term to decompose this

equation into:

Under an

equal value of life years gained as developed by Nord

et al., 1999 the authors assume that the quality of life improvement for

any life year’s gained is 1, (i.e., Q_At=1 in the first part of the

equation).

A new approach–Health Years in Total (HYT)–was proposed by Basu et al. (2021). HYT can be estimated starting with a similar decomposition, but Basu and co-authors assume that quality of life is equal to 1 for any survival gain in the second part of the equation.

Examples

of how to calculate these values can be found in a spreadsheet here.

Although

it appears that the authors are now double-counting quality of life gains that

occur during survival extension time period, the authors argue that this is not

the cas since they assume that quality of life and survival gains are separate in

nature and there is a linear substitution between then. The specific axiomatic foundation of HYT

requires two key assumptions:

utility independence and constant proportional

trade-off.

- Utility independence. Preferences over lotteries on longevity do not depend on fixed

health levels and conversely that preference over lotteries on health levels do

not depend on fixed longevity. - Constant proportional trade-off. Implies that the fraction of a person’s

remaining life that the person would trade-off for a given improvement in health does not depend on

the number of years of life that remain

Looking

at these

examples, HYT has the advantage over QALYs in that survival gains that accrue

to very sick individuals are not downweighted due to these individuals having

lower quality of life. In fact, HYT operates

very similar as the equal value of life years gained (evLYG) approach. The main difference between HYT and evLYG occurs

when there quality of life improvements occur differentially in the period over

which the standard of care occurs and the survival period over weight the new

treatment improves survival. Note that HYT

does place less value on treatments that generate only quality of life gains,

but no survival gains. In these cases,

HYTs gained would be equivalent to QALYs gained but the value of an HYT gained (which

ranges between 0 and 2) is less than the value of a QALY (which ranges from 0

to 1).

A key

question is what willingness to pay threshold should be used with HYT. The authors use the Tufts cost effectiveness

analysis registry and find that commonly used thresholds of $50,000, $100,000

and $150,000 per QALY correspond to the 53rd, 71st and 78th

percentiles in terms of the log cost per incremental QALY distribution. The corresponding figures for the log cost

per incremental HYT are $34,000, $74,000 and $89,000 respectively; this values

are very similar to the evLYG approach.

When considering these 3 metrics—cost per incremental QALY, cost per evLYG, cost per HYT gained—each has their pros and cons. In my opinion, however, HYT should be considered a modification of the evLYG framework that has the benefit of taking into account in some fashion quality of life benefits that accrue during the extra survival years. None of these metrics are perfect, but each of them is useful.