By VINCE KURAITIS and SETH JOSEPH

Let’s start with a pop quiz. Take 15 seconds to look at the list below, asking yourself the question “What do all these have in common?”

- address books

- video cameras

- pagers

- wristwatches

- maps

- books

- travel

- games

- flashlights

- home telephones

- cash registers

- MP3 players

- Day timers

- alarm clocks

- answering machines

- The Yellow Pages

- wallets

- keys

- transistor radios

- personal digital assistants

- dashboard navigation systems

- newspapers and magazines

- directory assistance

- travel and insurance agents

- restaurant guides

- pocket calculators

The commonality is that all of these were disrupted by smartphones and their operating system (OS) platforms — Google Android and Apple iOS.

Let’s consider a healthcare comparison. Ask yourself, “What do all these have in common?”

- Primary care

- Urgent care

- Office visits

- Hospitals

- Inpatient

- Outpatient

- ER

- Specialist access

- Behavioral health

- Diagnostics

- Patient portals

- Home health services

- Medication administration

- Preventive care

- mHealth apps

- EHR functionality/apps, e.g.,

- Scheduling & check in

- Billing

- eRX

- Medication management

- Referral management

- Care planning

- Care coordination

- Social care

- Patient education

- Patient communications

The commonality is that all of these are potentially disruptable by Virtual Care Platforms (VCPs).

In this essay we ask the question “Will virtual care platforms become healthcare’s mega-platforms?” We believe the potential for such a scenario is strong. We describe and assess parallels between the evolution of the duopoly smartphone operating system (OS) market and the emerging virtual care platform market. Our intent is to describe a plausible scenario for the future – not to make a prediction.

Background

A 2020 McKinsey study estimated that $250 billion of healthcare could be virtualized. Examples of virtual care platform vendors include Teladoc, Amwell, MDLive, Amazon Care, and many others.

We’ll use the acronym “WTA” as shorthand for “winner-take-all (or most)” markets. More generally, we’re referring to markets that become highly concentrated — a monopoly (one dominant firm), a duopoly (two dominant firms), or an oligopoly (a small group of dominant firms — typically three to six).

You’re probably familiar with other examples of dominant mega-platforms in WTA markets:

- Microsoft Windows in desktop PCs

- Facebook in social networking

- ebay in auctions

- Google and Facebook in digital advertising

- .pdf for documents

- Amazon in e-commerce

- Sony PlayStation, Microsoft Xbox, and Nintendo Switch in video game consoles

- Google Android and Apple iOS in smartphone OSs

However, we haven’t (yet) seen dominant mega-platforms in healthcare. Some factors that explain the lack of mega-platforms in healthcare include industry fragmentation, misaligned economic incentives, heavy regulation, and the complexity and size of the industry — approaching 18% of GDP.

A growing body of economic analyses have discerned industry characteristics that produce WTA markets, e.g., here, here and here. These industry characteristics include:

- A tendency toward single homing (users preferring one platform)

- Existence and strength of network effects

- High switching costs

- Demand for differentiated platform functionality

Smartphone Operating System Platform Wars

The smartphone OS platform war took place roughly between 2006 and 2016. In 2006, there were 12 operating systems for smartphones. By 2009 only 5 of these were still viable in the race.

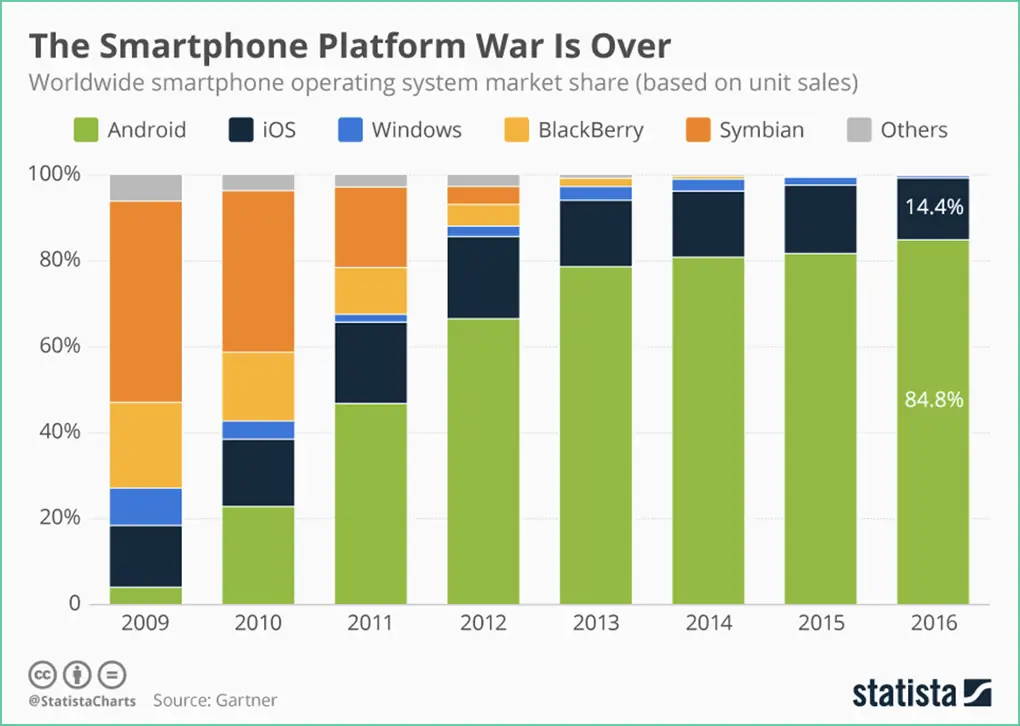

By 2016, the smartphone OS platform war was over — Android and iOS had won. As shown in the graphic below from Statista, Android had 85% market share and iOS slightly over 14%.

We learned many lessons from the smartphone OS platform war:

- Initial denial of the potential for disruption

- The power of platforms – the magnitude of the disruption and the range of adjacent technologies that were disrupted (see the list at the beginning of the article)

- Speed of disruption

- Power of open APIs and the power of network effects created through applications

- More than one route to success. The focus of iOS is to sell Apple hardware, whereas Android extends the tentacles of Google’s business model in search and advertising.

- Few winners, many losers

Comparing Smartphone OS Platforms and Virtual Care Platforms

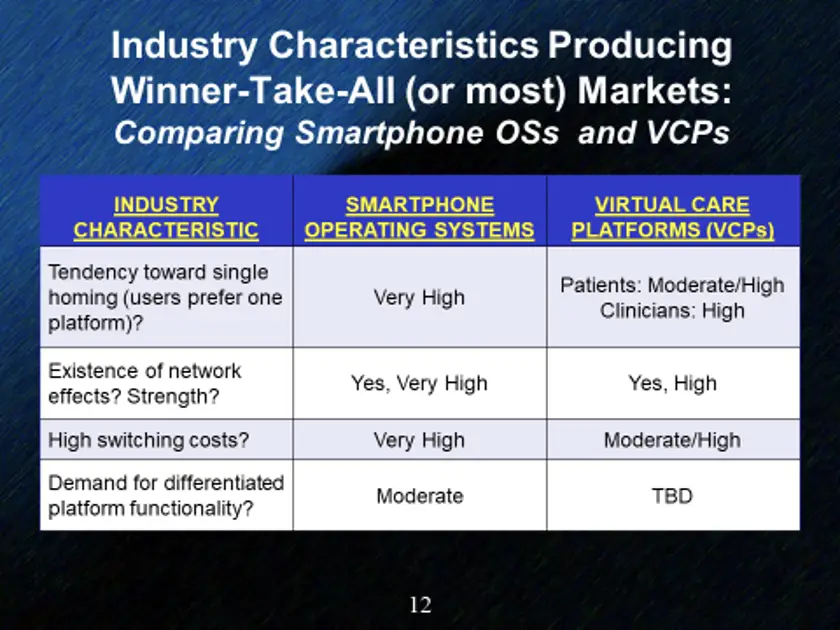

We see many of the dynamics of the smartphone OS platform war as being similar to the emerging VCP war. In the table below 1) the left column lists industry characteristics that produce WTA markets, 2) the center column summarizes how these characteristics played out in the smartphone OS wars, and 3) the right column displays our take on how these characteristics have potential to play out among virtual care platforms.

Let’s take a closer look. The VCP market is very early, so much of our take is based on possible or likely market evolution.

Tendency toward single-homing. “Single homing” describes users’ preference to use one platform vs. multiple platforms (multihoming); this is decided by whether users gain more utility from one platform or by simultaneously using two or more platforms. Platforms where users tend to have single “homes” include: computer operating systems, ISPs, cable TV, and video game consoles. Examples where consumers are comfortable with multiple “homes” include: credit cards, securities brokerages, subscription video services, and magazines.

For smartphone OSs, almost all users have a strong tendency toward single homing, i.e., they’ll choose to use either Android or iOS, not both.

How will single vs. multihoming play out with VCPs? Let consider different sides on VCP platforms — patients and clinicians.

Today, it would be only moderately inconvenient for patients to use multiple VCPs; the user interfaces will have slightly different features but also will have a lot of commonality.

In the long-term, VCPs have the opportunity to develop feature sets that encourage single homing. For example, today’s patient portals essentially force patients to multihome, e.g., “My mom has seven different portals from seven healthcare providers”. Patients would prefer to have a single home on one portal, but for most patients today that’s not possible. Could VCPs evolve to become the single patient portal for which patients yearn?

On the clinician side of the platform, we see the tendency toward single homing as being high, even today. Clinician workflow will be most efficient and smooth when working on one platform. VCP vendors likely will reinforce the tendency toward single homing by non-compete clauses in their contracts with clinicians.

Existence and strength of network effects. Network effects have been responsible for 70% of all the value created in technology since 1994. Nfx has identified at least 13 different types of network effects.

In the case of smartphone OS platforms, perhaps the strongest is cross-side network effects which arise from complementary goods or services in a network with more than one side. Android and iOS both gain tremendous value and defensibility from their app stores. Today, Android has over 3 million apps and iOS has over 2 million.

For a while (≈2008 to 2012) it looked like Windows Mobile might become a viable 3rd platform in the smartphone OS war. Ultimately, a major reason for its failure was an inability to attract enough app developers. Thus, one way to characterize the smartphone OS war was as a battle for developers and the complementary apps they created as much as a battle for end users.

The VCP market also has potential for strong cross-side network effects. Platforms are beginning to compete on having a wide range of clinical providers and technical capabilities — some of which will be developed internally and others that will come from third parties. For example, Amwell recently announced a new open architecture technology platform and new capabilities from partnerships with Google Cloud, TytoCare, The Clinic, Biobeat, and Solaborate.

Will VCPs open app stores? We can foresee this possibility. Amwell’s new open architecture platform is a major step in that direction.

In the introduction to our article, we listed a number of capabilities/features that traditionally are associated with EHRs and EHR apps: scheduling & check in, billing, eRX, medication management, referral management, care planning, care coordination, social care, patient education, patient communications, and others.

Can you foresee that these capabilities/features become incorporated into VCPs? We can.

Can you foresee that VCPs compete for developers? We can.

We also see data network effects as being prevalent and powerful for VCPs. Data will create a strong flywheel effect — a platform with more patients will have more data, more data will facilitate more and better analyses, better analyses will fuel better clinical protocols which in turn will attract more patients.

High switching costs. Switching costs are incurred when consumers switch from one platform to another.

The switching costs for smartphone OSs are very high. Major costs include buying new smartphone hardware, purchasing and installing new apps, and time spent learning a new OS. Android and Google built walled gardens attempting to keep consumers inside their respective ecosystems.

Today the switching costs for patients going from one VCP to another are not particularly high. Over time, we believe VCP companies also will attempt to build walled gardens. In the classic book Information Rules, Shapiro and Varian describe many tactics that companies can employ to increase consumer switching costs: contractual commitments, durable purchases, brand specific training, information and data bases, specialized suppliers, search costs, and loyalty programs.

Some of these are already beginning to emerge in VCPs: health plans and employers are incentivizing consumers to use specific VCPs; VCPs are incorporating remote monitoring devices which patients will have to purchase; VCPs are supporting virtual primary care programs in which patients can develop an ongoing relationship with one physician.

Demand for differentiated platform functionality. There are times when different feature sets and capabilities are important to different categories of consumers. An often cited example is the video gaming console industry where three platforms with unique features — Sony PlayStation, Microsoft Xbox, and Nintendo Switch — were left standing. Another example is two social networking platforms that appeal to widely different audiences—Facebook and LinkedIn. When differentiated features are important to consumers, a larger number of platforms can co-exist in a market.

The smartphone OS platform market started with a dozen companies. Over time many of these platforms lost because they were not perceived as offering different or better features or capabilities.

It’s not difficult to foresee a VCP market where companies offer functionality far beyond the video visits that fueled their rise when the COVID-19 pandemic arose. One reason Teladoc acquired Livongo in 2020 was to integrate their chronic disease management capabilities. Other capabilities and features being added by VCPs include remote patient monitoring, an increasingly wide range of clinicians, second opinion offerings, and others.

What’s less clear is whether these varying features will be perceived as differentiated by patients and other platform purchasers (e.g., health systems, health plans, employers). KLAS analyst Mike Davis described the current market as having “lots of players, little differentiation”.

We believe it’s likely that over time some platforms will develop unique, specialized features. For example, Amwell’s business model is targeted heavily toward selling platform technology to health system customers who provide their own virtual care services, whereas Teladoc is selling both technology and services to a wider audience that includes patients themselves, health plans, employers, and health systems.

Summing Up

Let’s revisit the original question: “”Will virtual care platforms become healthcare’s mega-platforms?”

We believe such a scenario is highly possible, although not certain. Our best guess is that in 10 years the VCP market will be a highly concentrated oligopoly with perhaps 4-6 dominant companies. We believe that a monopoly or duopoly market is less likely; while the VCP market has much in common the smartphone OS market, the industry characteristics leading to WTA are somewhat weaker.

There are many unknowns. For example: many state and federal telehealth regulations were relaxed during COVID-19; which ones will persist? Medicare and many commercial health plans reimbursed telehealth at parity during COVID-19; what will reimbursement look like in the future? Could consumer demand for virtual care create a tipping point toward value based care and payment? Will VCP companies develop and execute effective strategies?

The smartphone operating system platform market taught us important lessons about the speed of disruption and the range of adjacent industries that can be affected. Will healthcare VCPs follow this path? Time will tell.

Vince Kuraitis, JD/MBA (@VinceKuraitis) is an independent consultant with over 30 years’ experience across 150+ healthcare & tech companies and blogs at e-CareManagement.com.

Seth Joseph is Managing Director of Summit Health, LLC, a boutique management consulting and strategy firm specializing in platform business strategy in healthcare; he is also a contributor to Forbes.