Here’s a potentially important paper that’s out in Science and is getting a lot of attention. The wide variation in severity of coronavirus infection has been noted throughout the pandemic, and we already know about a few of the risk factors: age, of course, but also being male, and having pre-existing conditions such as obesity and heart disease (which are, of course, often found in the same patients).

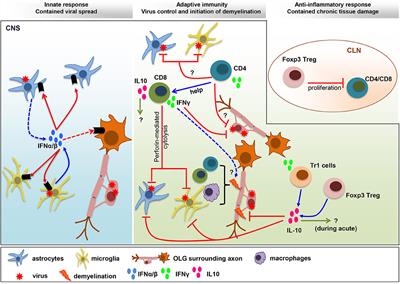

This new work, with a huge team behind it from more than 70 institutions, suggests another one: auto-antibodies to endogenous interferons. Everyone will have heard of interferon in a general sense, but getting a real understanding of that system is another thing entirely, which we can stipulate is true about immunology in general. There are three broad classes of interferon in humans (Types I, II, and III) and a bewildering network of functions and crosstalk between them. Suffice it to say for now that they are proteins whose synthesis is generally induced by some sort of viral or bacterial infection, and they go on to modulate a wide range of immune functions and affect the transcriptional activity of hundreds of different genes downstream. They’re of great interest not only in infectious disease, but in cancer and autoimmune disease as well, and we’re still working out all the pathways involved.

It’s been known for many years that some people have inborn mutations in one or another of these interferons, with bad consequences for their response to infectious pathogens. How the human genetic background changes the course of infection and inflammation is a vast and complicated field, but here’s a recent review from experts Jean-Laurent Casanova of Rockefellar and Laurent Abel from Paris (who are part of the current paper as well). Past such inborn protein errors, that are also people who have developed an inappropriate immune response to their own interferon proteins – they have autoantibodies circulating in their blood that neutralize certain interferons when they’re produced. For reasons that are still being worked out, at some point the immune systems of such patients have been activated against these interferon types as if they were foreign proteins, and unfortunately we don’t have many techniques for resetting that sort of thing. Disease of immune tolerance such as lupus and APS-1 generally show this as one of the underlying factors.

Interferon signaling has also been found to be important in the human response to coronavirus infection, of course, both in the direct antiviral aspect and in the overactive-immune-response part later on as well. Several different trials are underway looking at various interferon types as therapeutic options, but these are complicated by the need for good timing during the course of the infection. The complexity of the field means that the clinic is really the only place that one can sort this out: hypotheses are thick on the ground in an area like this one, but you have to go run a controlled trial to shed any light at all.

In this latest work, the authors look for the intersection of these stories: pre-existing autoantibodies in coronavirus patients that neutralize one or more types of interferon. The results are striking: in 1,227 healthy controls, four patients were found to have such antibodies. In 663 patients with mild coronavirus infections, none were found at all. But in 987 severely ill patients, at least 101 of them had such antibodies against at least one of the Type I interferons (!) I hope that those four people identified in the first cohort are taking precautions, was my first thought, because it certainly looks like they in a newly identified risk group. Those numbers come out to p-values of less than ten to the minus sixteenth, which means that we all pretty much have to stand up take take off our hats – this one’s real. The anti-interferon antibody patients also skewed older, which suggests that the levels go up over the years (exactly what you don’t want, honestly).

37% of the 101 patients in this group ended up dying of the disease, which is also an extreme statistical red flag. In cellular assays, it’s been shown that interferons such as IFN-alpha2 can block the coronavirus from infecting human cells. But plasma from these patients with neutralizing anti-interferon antibodies reversed that and left the cells open to infection. So the mechanism checks out as well.

Interestingly, 95 of those auto-antibody patients were male, so this could also be one of the reasons why men add up to being a risk group of their own. You see many autoimmune disorders more commonly in women (which may be due to differences in the amounts of the transcription factor protein VGLL3), which is more expressed in women than men. This one breaks hard the other way. The connection here might be that VGLL3 promotes interferon responses, leading to a too-sensitive autoimmune situation, but autoimmunity to interferons themselves might be expected to run through a different mechanism entirely. (This last part is all my free bonus speculation; it’s not in the current paper).

So while not all severe COVID-19 patients have antibodies against interferon, having them seems to make a person far more likely to end up with a severe infection. We’ll doubtless find more risk factors as more research comes in, but I doubt if any of them will be more firmly established than this one just was. As the paper notes at the end, these results have direct clinical implications. First off, anyone who screens with such antibodies needs to take extreme precautions, because they are clearly at far greater risk of severe disease and death than the run of the population. Second, this means that treating such patients with alpha-interferon will be a doomed effort, but beta-interferon (currently being studied intranasally) might still work, because antibodies to that one were rare. And one could also consider treatments aimed at knocking down the immune response to the Type I interferons themselves, starting with straight plasma exchange to bring down the antibody levels. And at the same time, such patients should not be part of any convalescent plasma donation program. Should they actually recover, that is. . .