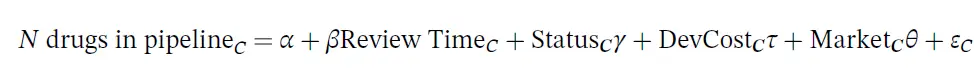

The dependent variable is the number of drugs in the pipeline for indication category, and the key independent variable is the natural log of the FDA review time for drug category C. The drug pipeline data comes from AdisInsight and the review time comes from the Drugs@FDA database. The regression also controls for whether the drug is receives priority or orphan status (also from Drugs @FDA), the development cost and the market size. The development cost is endogenous so the authors use the number of pages in an NDA submission, the number of Phase III clinical trials and the Phase III trial sample size. The vector of market characteristics include disease mortality and morbidity (from World Health Organization data by disease), all‐payer drug expenditures (from the Medicare Expenditure Panel Survey, MEPS); number of drugs on the market (also from MEPS); and drug prices (from Express Scripts/Medco and Redbook).

The authors find that:

The average FDA review time for drugs approved after 1999 is 466 days, or about 1.3 years, but …it takes anywhere from 46 days (Eloxatin) to 1827 days (Prialt) for a drug to complete the review process that gives a drug a green light to be marketed. Post‐PDUFA, many NDAs were eligible for a special review status. About a half of the drugs in our sample received a priority review status, and about 20% were classified as orphan, on average by disease category.

Using the regression specification described above, they also find that longer review time decreases the number of drugs in the pipeline.

A doubling of the review length is associated with approximately six fewer drugs in the development pipeline in that disease category. This implies that a one‐sixth increase in review length is associated with approximately one fewer drug in development; with a mean review length of 466 days, this implies that each 78 extra days of review are associated with one fewer drug in development.

One challenge of this study is that pipeline decisions are made years in advance. Thus, longer review time may also impact the decision for early phase drug development, but the data the authors use is from a fairly limited time period 1999 to 2005. Given that the drug development timeline is typically more than 10 years, this study estimates the impact over a relatively short time period. The study also ignores the regulatory process in other countries as well, and their impact on drug development. While the US is the largest pharmaceutical markets, the regulatory environment in other countries–particularly in Europe–may affect investment decisions.

Nevertheless, it is clearly logical that additional regulatory burden and delays in time to market clearly do affect this study does contribute to pharmaceutical firms investment decisions. Budish et al. (2015) find that firms often invest in oncology indications for late stage disease because the time for trials to read out is much shorter. To expedite the FDA review process, in 1992 Congress passed the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) which allowed the FDA to charge fees to pharmaceutical firms to expedite the review process. These payments fund just under half of all drug reviews.

This study does add to the literature on how pharmaceutical firm R&D respond to incentives. For instance, Acemoglu and Linn (2004) found that a potential market size affects affects the number of new drugs that get to market. Other studies have found that higher profits boost pharmaceutical firm R&D investments, for instance the advent of Medicare Part D (Blume-Kohout and Sood 2013) and changes in patent law (Williams 2017). Perhaps the best-known paper–Dubois et al. 2015–found an elasticity of innovation with respect to market size of 0.23, suggesting that $2.5 billion of revenue is required to bring a new drug to market based on drug development costs. The paper by Chorniy et al. (2020), despite some limitations, helps add to this literature.

Source:

- Chorniy A, Bailey J, Civan A, Maloney M. Regulatory review time and pharmaceutical research and development. Health Economics. 2020 Oct 19.